Squeeze and slide

Nihon, noted

Some immediate observations on the Japanese elections, which resulted in a remarkable landslide victory for Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, with her governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) gaining a supermajority in the lower house of the National Diet. This continues an occasional series of reflections on Japan from Japan, which seek to connect the general and the specific (one, two, three, four).

Let us start with a straightforward observation: people do not like being squeezed. This has had a noticeable impact on recent elections. 2024 was a story of incumbent parties being punished at the polls because of inflation. Recall this FT chart:

In Pew Research Center’s review of global elections in 2024, the authors judged:

What made 2024 such a tough year for incumbents? While every election is shaped by local factors, economic challenges were a consistent theme across the globe… Inflation was an especially important issue in this year’s elections…

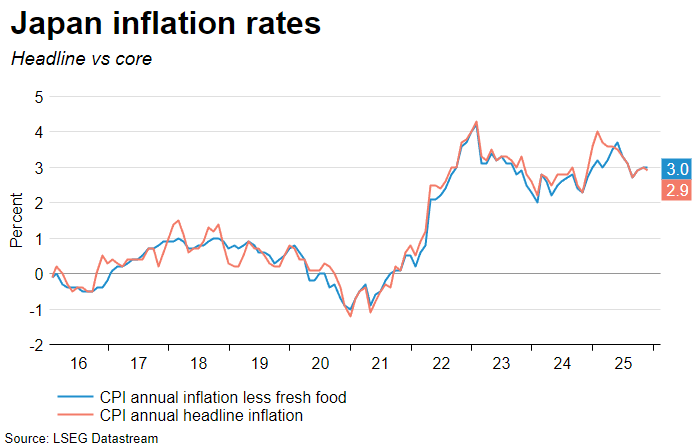

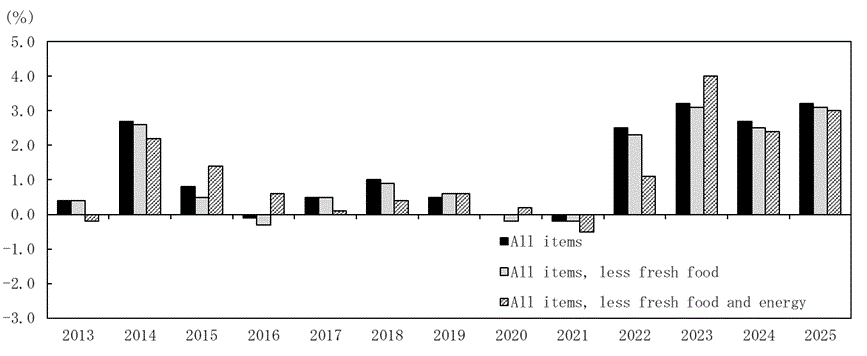

It is worth keeping in mind this widespread judgement that inflation was very bad for incumbent parties, as inflation has remained a serious source of stress for Japan. Care of Reuters:

And the Statistics Bureau of Japan:

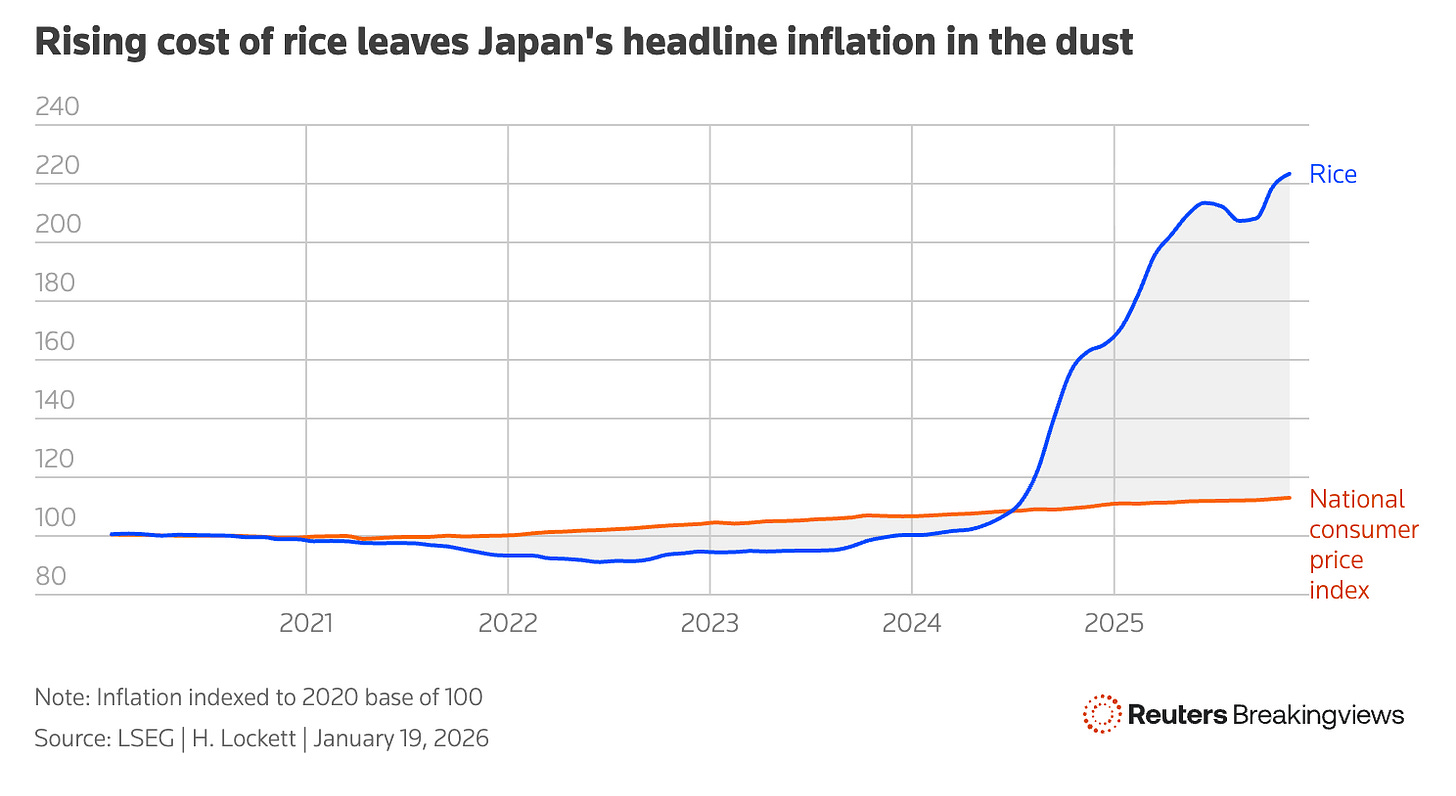

Japan has hardly been alone in experiencing inflation, but its arrival and persistence after decades of deflation and price stability has had a very noticeable impact. It is keenly felt. It is also important to zoom in on one item - rice - where a cocktail of bad policy, misaligned incentives and climate change has resulted in a significant surge in price, as this Reuters chart illustrates:

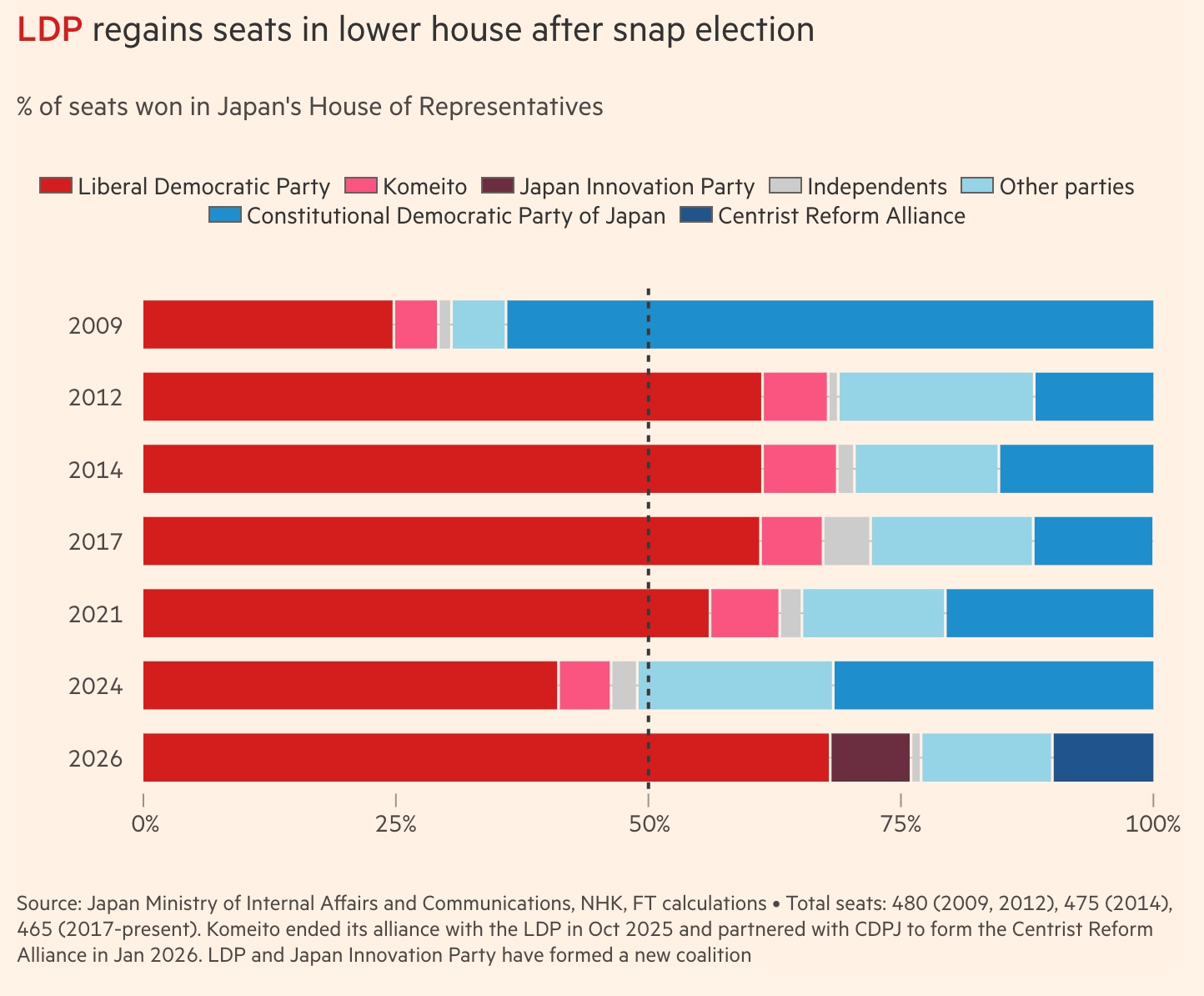

Joining these initial observations together: election results across the globe in 2024 - including in Japan - strongly suggested inflation led to incumbent parties losing votes and often ceding power. Japan is continuing to experience economic stress, especially in its most important staple, rice. Given this, one might have expected Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi and the governing LDP to again be punished, as it was in elections in 2024 and 2025. Quite the opposite happened, however, with a remarkable victory for the LDP, as this FT chart illustrates:

What explains this divergence? I would suggest that the underlying observation still holds: people do not like being squeezed. This squeezing might come from inflation, but it can also come from overbearing allies that impose tariffs and unreasonable demands, as well as aggressive neighbours that engage in economic coercion and threaten sovereignty.

It is here where it is possible to identify the most direct point of comparison: Mark Carney’s victory in the Canadian federal election in April 2025. A few months prior, the ruling Liberal party had been 20 percentage points behind in surveys, but this unpopularity was skilfully reversed and overcome by Carney. He replaced the unpopular Justin Trudeau, and campaigned on a platform that offered a clear and firm response to the threats made by US President Donald Trump. Strong leadership in response to being squeezed. Notice any similarities?

In October 2025, Takaichi replaced the hapless Shigeru Ishiba, who had led the LDP to consecutive defeats in lower house and upper house elections. Tobias Harris, a perceptive observer of Japanese politics, titled his overview on the 2025 upper house elections, ‘System in crisis’, and in another piece a few months later he suggested:

Japan’s political instability is likely to get worse before it gets better. The reality is that no party is able to muster a majority to govern the country.

These were valid judgements in the context in which they were made. The point in raising them now is to emphasise the remarkable turnaround of fortunes for the LDP under the leadership of Takaichi. As with Carney in Canada, the combination of robust leadership in response to being squeezed has proven to be a winning formula. Unlike Canada, however, Japan has had the pleasure of being squeezed not by one, but two not-so-great powers at the same time.

As to why the comparison between Carney and Takaichi has not been made, some of it is presumably due to banal reasons related to differences in who and where, but also the different stances the two have taken to American bullying. Carney’s approach is now exemplified in his defiant ‘rupture, not a transition’ address at Davos this year. In contrast, Takaichi has chosen to cosy up to Trump, resulting in his endorsement and support (so far). From afar, this might look like Japan simply adopting the position of supplicant. Placed within the Japanese context, however, it appears more as an attempt to revive the approach that former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe adopted towards Trump, which is widely seen as having been relatively successful. Compared with Ishiba, Takaichi seems better at making the most of a weak hand. This point was recently expressed in a podcast with Tomohiko Taniguchi, formerly a special advisor to Shinzo Abe and now Chairman of Nippon Kaigi and Professor at the University of Tsukuba:

There is no luxury… for Japan's leader to act just as the Canadian prime minister did, famously, over Davos meetings. It would be great if a Japanese prime minister could speak in blunt terms about Trump, but there is no luxury such as that. Canada may have one single country along its border, which is America, and they speak the same language. They share more or less similar cultures. And their economies are very much integrated with each other.

For Japan, no such environment has existed or will exist in the future. The need for Japan to ally firmly with the United States, like it or not, has gotten even more paramount and will be so in the coming years. So the first and the second and the third most important for the Japanese leader, whoever that would be, is to maintain a very good operational and military, as well as strategic, collaboration, cooperation with the United States.

Acknowledging this, it would be foolish to think that policymakers or the public are happy about this situation. America turning a deep partnership into a transactional one has been deeply disappointing for their counterparts. From the FT’s reporting on the trade deal Japan struck with the US: ‘one Japanese chief executive described the event as “a shakedown”. One diplomat described it as “street-level tactics”.’ Nonetheless:

Japan is keenly aware that it is in a precarious position. It relies on the US as an important defence ally as well as its largest export market, leaving it highly exposed to the threat of tariffs, particularly for its huge auto industry.

These dependencies and vulnerabilities might be dictating Japan’s response, but one should not be surprised if the Japanese are also not especially enamoured with such bullying. Yet Japan’s problem is that it is being simultaneously squeezed by its most important partner, the USA, and its most significant neighbour, China.

Japan’s uneasy relations with China took another turn for the worse in November when Takaichi said the quiet part out loud by acknowledging that a Taiwan contingency could amount to a ‘survival-threatening situation’ for Japan. This quickly triggered a strong response from China, which included Xue Jian, the consul general in Osaka, posting on X (8/11/25): ‘the filthy head that recklessly sticks itself in must be cut off without a moment’s hesitation.’ The reader can judge whether that would qualify as diplomatic language or not. China has expressed its displeasure with a series of political and economic measures, including restricting rare earths and tourists traveling to Japan. If this was a gambit to weaken Takaichi’s position, it would appear to have had the opposite effect. From Nikkei Asia’s coverage:

That approach [Chinese pressure] appears to have backfired, experts say, helping to propel the LDP across a key parliamentary threshold that could open the door to a much stronger Japanese defense posture. At the same time, Japanese political parties that prefer a softer stance toward China have been weakened considerably.

Shingo Yamagami, a former Japanese ambassador to Australia, described China as the "hidden agenda of yesterday's election." The outspoken retired diplomat wrote on X on Monday: "In light of belligerent actions & waves of economic coercion, should Japan acquiesce or stand tall? The Japanese people clearly chose the latter."

Faced with bullying and coercion from both the United States and China, one should hardly be surprised that the Japanese public are backing a leader who is proposing stronger measures on economic security and defence. This is where one must be cautious of headlines like this one from The Mainichi, ‘Takaichi’s election victory sets the stage for a rightward shift in Japan’s security policies’. The reality is more complicated. Japan’s direct neighbours include three nuclear powers: China, Russia and North Korea. One should not have to reflect especially long to consider why this might pose concerns for Japan, especially in the context of its key strategic partner embarking on some rather ‘interesting’ domestic and international policies.

In a piece reflecting on the campaigns waged by the different parties, Tobias Harris observes:

Takaichi, not unlike her political mentor Abe Shinzō, is refreshingly frank about her vision for Japan. She spends most of her speech talking about the need to raise investment in the interest of promoting national autonomy and self-reliance. While we can debate whether this is an inward turn or a “recalibration”, her message is, to borrow the words used by one of her advisers in a different context, “in the end we can only rely on ourselves.”

Not only did Takaichi’s message land well, but much of the opposition appeared completely out of date. Considering the platform presented by the co-leaders of recently formed Centrist Reform Alliance (CRA), which performed terribly, Harris further judges:

However, what is ultimately most striking about both Saitō and Noda’s remarks is how backwards looking they are. They both repeatedly refer to Japan as a “peace-loving nation” (平和国家), referring to the postwar legacy surrounding Article 9 of the constitution. They warn of the dangers of Japan being drawn into war under Takaichi. They defend the three non-nuclear principles and warn that with a large majority Takaichi will pursue constitution revision and “full spectrum” collective self-defense. Noda uses a portion of his remarks to discuss how policies pursued by the Koizumi and second Abe administrations made Japanese society more unequal. They both talked about Takaichi’s LDP moving to the right. But for many voters this rhetoric falls on deaf ears.

Given the available options, one can understand why so many voters chose to support the LDP once again. Takaichi’s platform is one that much more directly speaks to a more threatening world in which Japan is getting squeezed and needs to find better ways of protecting its interests.

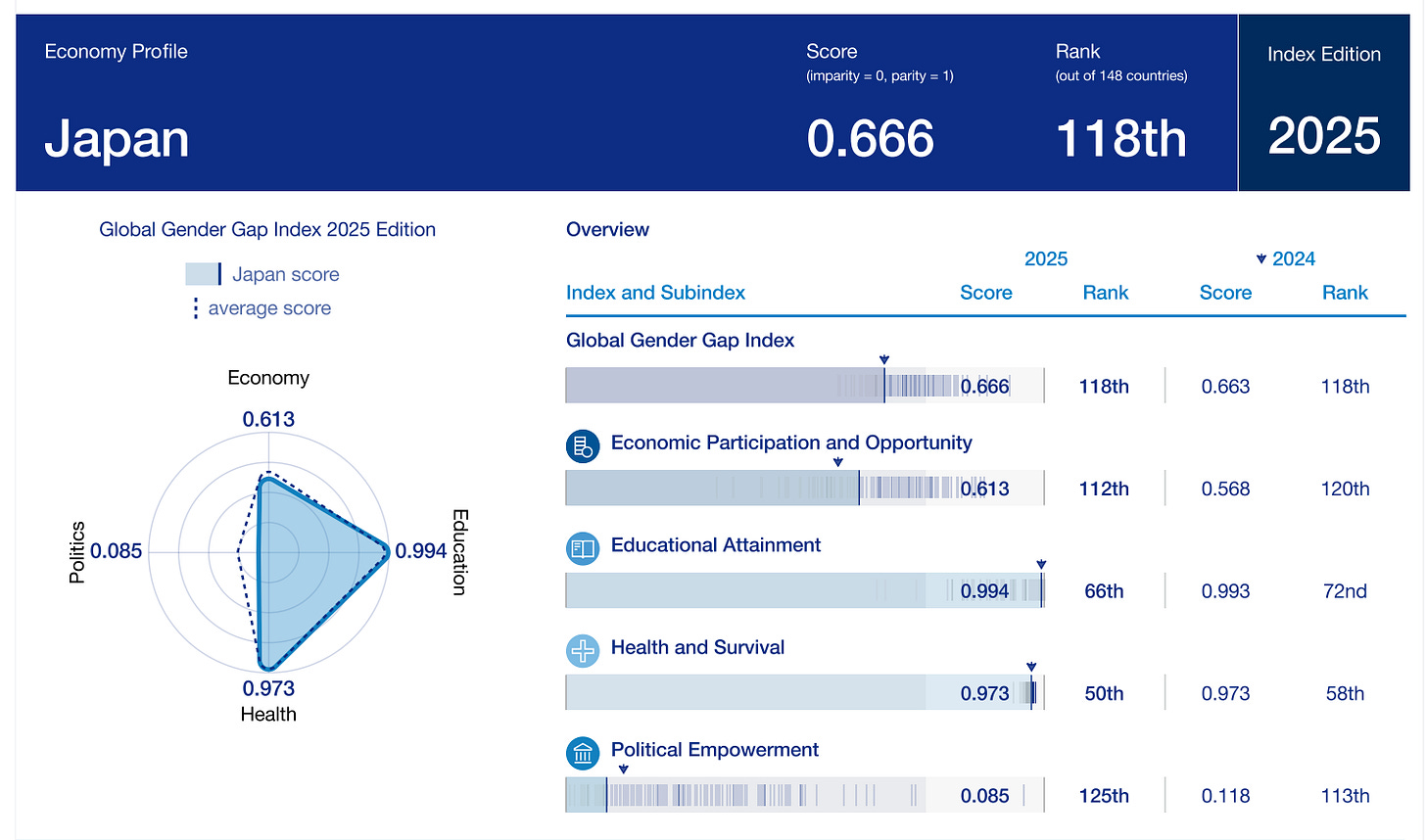

A final point about Takaichi’s appeal. Last October when Takaichi was voted in as the 104th prime minister of Japan, she became the first woman to hold this role. For some context, consider Japan’s position in the WEF’s Global Gender Gap Report 2025, which could be summarised as ‘not good’:

Alongside this, there are two related biographical features that are relevant: she did not graduate from one of the top Tokyo universities that normally supply politicians, and she is not from one of the dynastic families that regularly produce leaders. Put together: Japanese politics has been overwhelmingly dominated by men with powerful family relationships and deep university networks. Takaichi had to work to overcome these three separate, and closely related, disadvantages. Japanese power structures are very deep, very rigid, and very hard to break into and through. I would suggest that many Japanese - especially younger people - are keenly aware of what an achievement it is for Takaichi to have made it to the top. This is not insignificant.

Takaichi winning the leadership of the LDP, becoming Prime Minister, and now delivering a sizeable electoral victory suggests she has political acumen and luck, both of which are needed when in power. There are certainly aspects to her platform that are a bit off / ちょっと, but it would be an overstatement to present these electoral results as a simple rightward lurch. Whether inflation or bullying, publics do not like being squeezed. In a comparable fashion to Canada backing Carney, it would appear that the Japanese electorate sees in Takaichi a leader better equipped than the alternatives for trying to guide the country through a difficult and dangerous period. All things considered, this would seem like a good bet to make.

Much more could be said, but that is enough for one note. If any readers are unhappy about my failure to discuss Japanese debt and JGBs, I would recommend this excellent collection of charts presented by FT Alphaville.

Apologies I still need to provide more information about the new format for these notes going forward. I decided to prioritise this more timely discussion. As of now, new notes will be available for two weeks before being archived alongside older notes behind a paywall. I’ll subsequently transition to a model with most notes only available to those with a paid subscription. More details to follow.