On and off target

Nihon, noted

After the Lower House elections in Japan last October, I wrote a note that emphasised the mounting and cumulative stresses on the country.

Many of dynamics described last year have persisted, some have deepened: a weak yen, sustained inflation - most notably in rice, climate extremes and the extreme awfulness of over-tourism, Chinese vessels and aircraft continuing to push up to the edges and into Japanese territorial space, the rising influence of social media on politics, all alongside increasing exasperation with a tried and tired LDP and its unconvincing Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru. To which has been added doubts and uncertainties as a result of the second Trump administration. At the end of that note I observed:

Japan remains fortunate that there has not been much uptake in populism and extremism, even if fringe parties did make some gains.

While many of these problems are quite specific to Japan, they are a reflection of dynamics that are posing challenges to governments everywhere. More and more stresses are piling up on systems that have less capacity to respond and reduced freedom to move.

With the Upper House election due in a few days on 20 July, it looks like Japan is on track to continuing its path towards ‘normality’, with populism and social media’s impact being more keenly felt. The Economist surveys the field:

Party members are starting to sound fatalistic about what the coming years will bring. “Maybe people are just getting tired of the LDP itself,” one of its bigwigs reflects. The party has been making efforts to appear more energetic. During last year’s Lower House campaign, its slogan was “Protect Japan”; for the Upper House ballot, it has switched to “Move Japan”. Yet it has still not stated very precisely where it would like the country to go.

Newer, smaller parties are offering clearer messages, even if their ideas are often impractical. Several outfits now threaten the LDP from the right. The Do it Yourself Party (Sanseito), a five-year-old far-right populist party, has made inroads with an anti-immigrant “Japanese First” message. The Japan Innovation Party (Ishin) has built up a strong base around Osaka, Japan’s second city. There are left-wing upstarts, too. Reiwa Shinsengumi, a six-year-old populist party, is trying to steal voters from the staid Japanese Communist Party and the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP), the centre-left successor to the DPJ. It promises, among other things, to abolish the consumption tax.

As Tobias Harris outlines, a poor performance by the ruling LDP and advances by populist candidates appears highly likely. If there is one thing that politicians discovered in 2024, it is that electorates do not like inflation. Recall the FT chart that did the rounds:

With that in mind, consider this chart from Reuters on current inflation in Japan:

Leo Lewis in the FT has a strong piece that emphasises the centrality of the weak yen:

Its prolonged stint below ¥140 to the dollar is producing various effects, including the sense of national diminution that comes with seeing that your currency is no longer the mighty force that once shook the world. Developed country comparisons of average incomes make Japan’s look risibly low in dollar terms; the suggestion that Japanese wages now trail those higher-end earners in Thailand and Indonesia is an even harder blow.

The more politically potent impact is inflation. After years of deflation, Japan has had three years of sustainably rising prices but for the wrong reasons: cost-push inflation driven by the weak yen and the fact that it imports a high proportion of its raw materials, food and energy.

The strain on households is real. Japan’s Engel coefficient, which measures food as a proportion of household spending, is at a 43-year high and inflation-adjusted wages fell for a fifth straight month in May. The most consequential policy battleground of the election — a cut to VAT — attests to real household pain.

All of this might be slightly more palatable if the outside world were not so visibly revelling in the yen’s weakness — picking off industrial gems at the corporate and private equity level, and gorging on sushi and ski resort property at the individual one.

Prices for modest luxuries like restaurant dining, at which the Japanese now balk, are irresistibly low for the record 18mn tourists who visited the country between January and May. At the same time, Japanese real estate is being bought by foreigners at unprecedented rates. The two flows of foreigners — tourists and longer-term immigrants — are being successfully conflated by Sanseito and others to look like a single exploitative incursion.

These imbalances are really real, and really felt. The government’s stated goals for some time have been more inflation and more tourism. It has them now and people are not happy.

These conditions made me recall a part of Stefan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday, where he described the collapse of Austria’s currency after the great war:

Austria was “discovered” and suffered a calamitous “tourist season.” … The tidings of cheap living and cheap goods in Austria spread far and wide; greedy visitors came from Sweden, from France; more Italian, French, Turkish and Rumanian was spoken than German in Vienna’s business district.

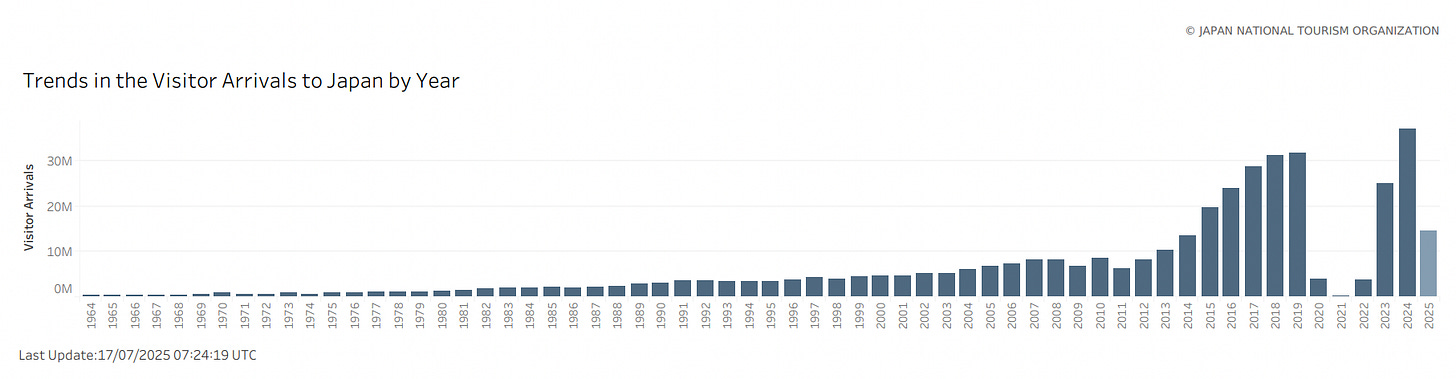

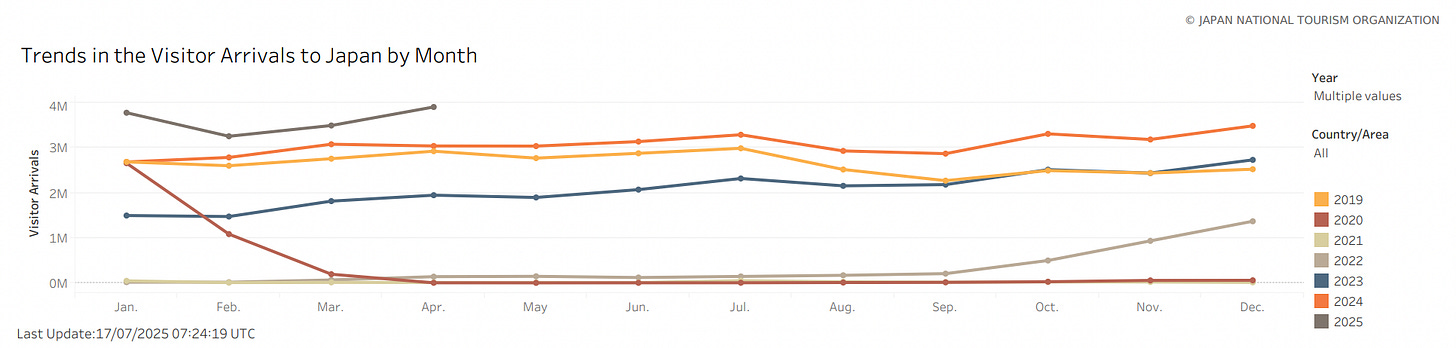

Returning from Vienna to Tokyo, the amount of tourism is very evident and very unpleasant. In the first half of 2025, Japan experienced a record 21.51 million visitors, a 21% increase on the same period last year. This certainly benefits some, with a record of 4.8 trillion yen ($32.23 billion) spent, a 22.9% year-on-year increase. At this rate, the country is on target to achieve the government’s ‘goal’ of 60 million visitors by 2030. Excellent.

Lewis rightly highlights how the weak yen is connected to the problem of over-tourism, but the other major issue is speed and scale. Too many people, too fast. Japan went from the closed borders of the pandemic to record numbers of tourists in two years. This is not healthy. The problem is easy to see in these graphs:

What is not captured in these graphs is how poorly distributed these numbers are. The vast majority of these people are going to the same places in the same cities. The aggregating feature of the apps relied on when travelling pushes everyone to the same spots, the same restaurants, the same ‘experiences’. In a balanced and thoughtful piece, Craig Mod speaks to these dynamics:

At risk of oversimplifying: Most “problems” in the world today boil down to scale and abstraction. As scale increases, individuals become more abstract, and humanity and empathy are lost. This happens acutely when the algorithm decides to laser-beam a small shop with a hundred-million views. If you cast a net to that many people, a vast chunk of them will not engage in good faith, let alone take a second to consider the feelings of residents or owners or why the place was built to begin with. Hence: The crush, the selfish crush.

Overtourism brings with it a corollary effect, what I call the “Disneyland flipflop.” This happens when visitors fail to see (willfully or not) the place they’re visiting as an actual city with humans living and working and building lives there, but rather as a place flipflopped through the lens of social media into a Disneyland, one to be pillaged commercially, assumed to reset each night for their pleasure, welcoming their transient deluge with open arms. This is most readily evident in, say, the Mario Kart scourge of Tokyo — perhaps one of the most breathtakingly universally-hated tourist activities. I dare you to find a resident who supports these idiots disrupting traffic as the megalopolis attempts to function around them.

Indeed. I would assume most people are rather supportive of the recent attempted arson of one of these go-kart operations. Perhaps it is time for a GoFundMe page…

Continuing with Mod’s piece:

This overtourism is happening mostly because of algorithms collimating the attention of the masses towards very specific activities / places. There’s also a slightly nutty narcissism / selfish component to it, too — fueling that impulse to, at all costs, “get” a photo at a specific spot to share on a specific social media service. (See: Fushimi Inari.) If the algorithm is the gas, cheapness is the spark. Because, damn, is it cheap to travel these days. Combined with the fact that there have never been more “middle class” people in the world, and you get overtourism. In a way, overtourism complications and disruptions are what happens when “humanity wins” and more people have more time and money to go “do things.”

Recall the Adorno quote that Malm and Carton emphasise in Overshoot:

Seven words from Theodor Adorno summed up the situation: ‘society is not in control of itself.’

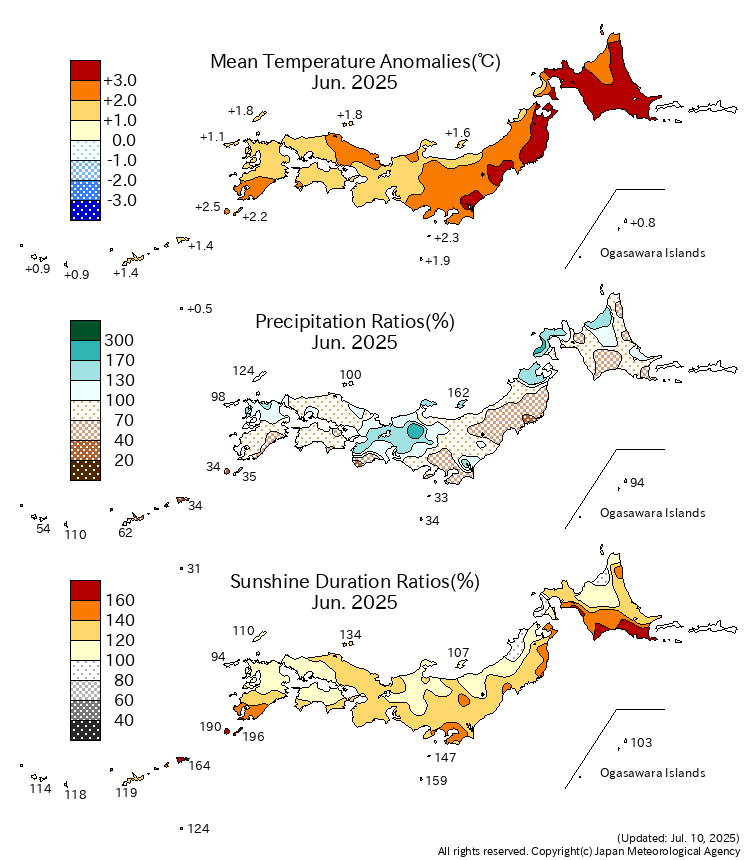

This points towards another ambient factor relevant to the elections: heat, oppressive heat. Last month was the hottest June in Japan since record-keeping began in 1898. It is captured in this Japan Meteorological Agency map:

How directly these conditions might impact voter sentiment is a question I will leave to others, but my assumption is that it is one more thing contributing to the discontent and frustration in the air.

The climate sits alongside other major macro trends present: the uncertainties and changes brought about by an increasingly erratic US, to which Japan remains closely tethered; the consistent and insistent pushing of territorial boundaries by China, the larger neighbour Japan must find a way to live with; and an increasingly wobbly bond market, with Japan threatened by its own variant of the ‘moron premium’.

In a prior note, I proposed an ‘Anna Karenina reading of international politics’, in which, ‘each unhappy country is unhappy in its own way’. Cute and acute, perhaps partly accurate too. What this note has sort to highlight is some of the sources of Japan’s unhappiness, and the likelihood of that unhappiness deepening in the short-term.

As a way of finishing, let us return to Austria and Zweig’s recollections. The passage continues with what he describes as a ‘ precise reflection, in grotesque graphic miniature, of the whole insane character of those years.’ The virtue of offering it here is less that it speaks directly to present conditions in Japan, and more that it offers a reminder of those times in history when absurdity and possibility bend and blur together in a distorted reality that is all too real:

Even Germany, where the inflation started at a much slower pace even if eventually to become a hundred thousand times greater than Austria’s, exploited our shrinking krone to the advantage of her mark. Salzburg, a border town, afforded me an opportunity to observe these daily raids. Bavarians from neighboring villages and cities poured into the little town by hundreds and by thousands. They patronized the tailor, they had their cars repaired, they consulted physicians and bought their drugs. Munich businessmen mailed their foreign letters and filed their cables from Austria so as to pocket the saving in the rates. Then, at the instigation of the German Government, a border control was established to stop Germans from buying their supplies in Salzburg where a mark fetched seventy Austrian crowns. Merchandise coming from Austria was strictly confiscated at the custom house. One article, however, that could not be confiscated remained free of duty: the beer in one’s stomach. And the beer-drinking Bavarians would watch the daily rate of exchange to determine whether the falling krone would allow them five or six or ten liters of beer in Salzburg for the price of a single liter at home. No more superb enticement could be imagined, and so they would come in hordes with their wives and children from nearby Freilassing and Reichenhall to enjoy the luxury of gulping down as much beer as belly and stomach would hold. Every night the railway station was a veritable pandemonium of drunken, bawling, belching humanity; some of them, helpless from overindulgence, had to be carried to the train on hand-trucks and then, with bacchanalian yelling and singing, they were transported back to their own country. The merry Bavarians did not, to be sure, suspect how terrible a revenge was in store for them. For, when the krone was stabilized and the mark in turn plunged down in astronomic proportions, it was the Austrians who traversed the same stretch of track to get drunk cheaply, and the spectacle was duplicated but this time in the opposite direction. This beer war between two inflations remains one of my oddest recollections because it was a precise reflection, in grotesque graphic miniature, of the whole insane character of those years.