Zooming in, zooming out

Nihon, noted

The main story now coming out of Japan is who lead the country following Shigeru Ishiba stepping down. Sanae Takaichi has been elected the leader of Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), but following the end of its coalition relationship with the Komeito party, it has been unclear whether the LDP can secure enough votes to ensure Takaichi becomes Prime Minister. It now appears likely that the LDP with form an alliance with Ishin, the Japan Innovation Party, allowing Takaichi to become the country’s first female PM. This might be an important and overdue milestone, but there are few signs that Takaichi or the LDP have the creativity and capacity needed to meet the challenges facing them.

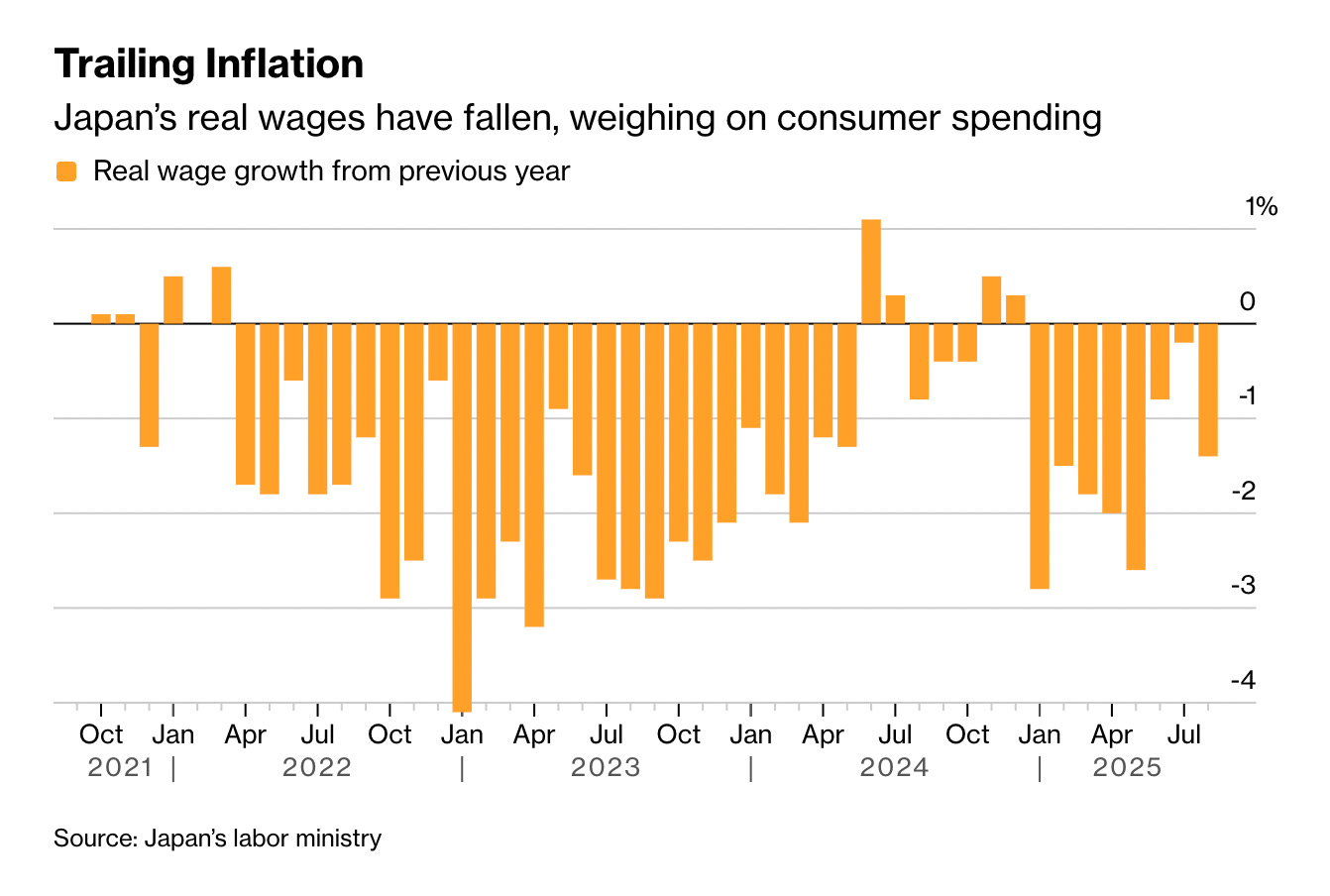

After desiring inflation for so long, it has finally and firmly arrived in Japan. This is having a real and felt impact on daily living, remaining the most immediate issue:

Tobias Harris sums up the poor state of Japanese politics at present:

Japan’s political instability is likely to get worse before it gets better. The reality is that no party is able to muster a majority to govern the country. It is unlikely that weak governments will be able to make some of the politically difficult decisions about fiscal consolidation, defense spending, social security reform, agriculture reform, and other pending questions. It also means that Japan’s voice could be missing in efforts to shore up regional and global institutions with Japan’s peer democracies. Of course, the failure of established parties to govern may create more room for an anti-establishment party like Sanseitō to gain more support.

While there are certain historical and contextual aspects, much of this is a Japan-specific version of more general trends of democratic malaise and weakness. In particular, Colin Crouch’s arguments in Post-Democracy about politicians becoming divorced from the publics they are meant to represent, alongside Wolfgang Streeck’s analysis in Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism in which there are crises without resolutions, resulting in problems being pushed away and piling up. Peak Streeck is a decade old, but only rings more true now:

Whatever governments do to solve a problem sooner or later produces another; that which ends one crisis makes the others worse; for every hydra head that is lopped off, two more grow in its place. Too many things have to be tackled at once; short-term fixes get in the way of long-term solutions; long-term solutions are not even attempted because short-term problems take priority; holes keep appearing that can be plugged only by making new holes elsewhere. Never since the Second World War have the governments of the capitalist West looked so clueless; never behind the façades of equanimity and tried political craftsmanship have there been so many indications of blind panic.

Alongside the many holes that globalisation and financialisation have put in state-based democracy, the disintegrative consequences of social media and smartphone-dependent people are becoming more and more evident. Japan is experiencing its own version of these more general dynamics.

In a prominent essay in the LRB in April, Perry Anderson presented an updated and largely compatible analysis, even if it almost completely overlooks the role of digital technologies. While Anderson is focused on the US and Europe, it can be extended to Japan, albeit with an uneven time lag:

The neoliberal system of today, as yesterday, embodies three principles: escalation of differentials in wealth and income; abrogation of democratic control and representation; and deregulation of as many economic transactions as is feasible. In short: inequality, oligarchy and factor mobility. These are the three central targets of populist insurgencies. Where such insurgencies divide is over the weight they attach to each element – that is, against which segment of the neoliberal palette they direct most hostility. Notoriously, movements of the right fasten on the last, factor mobility, playing on xenophobic and racist reactions to immigrants to gain widespread support among the most vulnerable sectors of the population. Movements of the left resist this move, targeting inequality as the principal evil. Hostility to the established political oligarchy is common to populisms of both right and left.

No populism, right or left, has so far produced a powerful remedy for the ills it denounces. Programmatically, the contemporary opponents of neoliberalism are still for the most part whistling in the dark. How is inequality to be tackled – not just tinkered with – in a serious fashion, without immediately bringing on a capital strike? What measures might be envisaged for meeting the enemy blow for blow on that contested terrain, and emerging victorious? What sort of reconstruction, by now inevitably a radical one, of actually existing liberal democracy would be required to put an end to the oligarchies it has spawned? How is the deep state, organised in every Western country for imperial war – clandestine or overt – to be dismantled? What reconversion of the economy to combat climate change, without impoverishing already poor societies in other continents, is imagined?

This is the context in which the shock and awe of China’s combination of 20th century Stalinism with 21st century high-tech ‘new productive forces’ now appears so imposing. As prior notes have considered, however, this could be a quite different variation of more generalised conditions of weakness. During China’s opening up period, the question was whether it could balance economic liberalisation with political control. It has managed this much more effectively than many assumed. Increasingly now the question appears to be whether China can balance its continued emphasis on export-led manufacturing growth at the expense of domestic consumption and trading partners.

Here one finds the intersection of two major trends placing great strain on Japan: the breaking, failing neoliberal democratic model alongside the ‘pincer movement’ described in the last note, whereby countries are caught in and between the malign machinations of the two not-so-great powers.

In reflecting on Japan’s relations with China, Tomohiko Taniguchi observed on ChinaTalk:

I call this phenomenon — remembering what it was called between Australia and Japan — a tyranny of proximity, not tyranny of distance. Tyranny of distance is something that Australians always used when describing the distance between their motherland, namely Britain and Australia, but China and Japan are very close together geographically. There’s a tyranny of proximity.

Taniguchi’s insight is a valuable one that can be extended and developed. Japan’s predicament is it suffers from the tyranny of proximity that comes being next to China, while also suffering from the tyranny of distance that comes from being allied with the US and aligned with the West more broadly.

The tyranny of distance operates between the US and Japan in a way that echoes the original Australian usage. The US remains an Asian power, but its homeland is elsewhere. The remarkable geographic advantages the US has gives it considerable buffer, and when combined with the power differential that was long clearly in its favour, it encourages a tendency to think - and act - in a rather loose and lax way about the possibility and consequences of using force elsewhere. Yet for Japan - and many others - that elsewhere is here. This is what Taniguchi points towards: China is immediate, present reality for Japan that cannot be avoided or confronted in some simplistic manner. Indeed, for East Asia, for the Asia Pacific as a whole, the idea of confronting China and the geopolitical kitsch of ‘Cold War 2’, a ‘new World War’, or a return to spheres of influence is profoundly limiting. Proximity means that the only option is some mode of living with China.

Japan must find ways to manage both its ‘tyranny of proximity’ with China, and its ‘tyranny of distance’ with the US. In particular, the latter is a significant challenge, as many institutions and actors remain firmly fixed within a US-centred and centric way of viewing the world that no longer accords with the behaviour and whims of Washington. Despite increasingly clear indications that its most significant alliance partner can no longer be relied on, there remains a deep hesitancy to fully confront what this means for Japan and its security. To return to Harris’ summation quoted above, there are few signs that the current possible political configurations in Japan have the capacity for the bigger and bolder thinking needed. This is a problem manifesting itself both in Japan, and more generally, there is a real sense that institutions and those attempting to lead them are struggling to adapt to a much more contested and conflictual reality now taking shape.

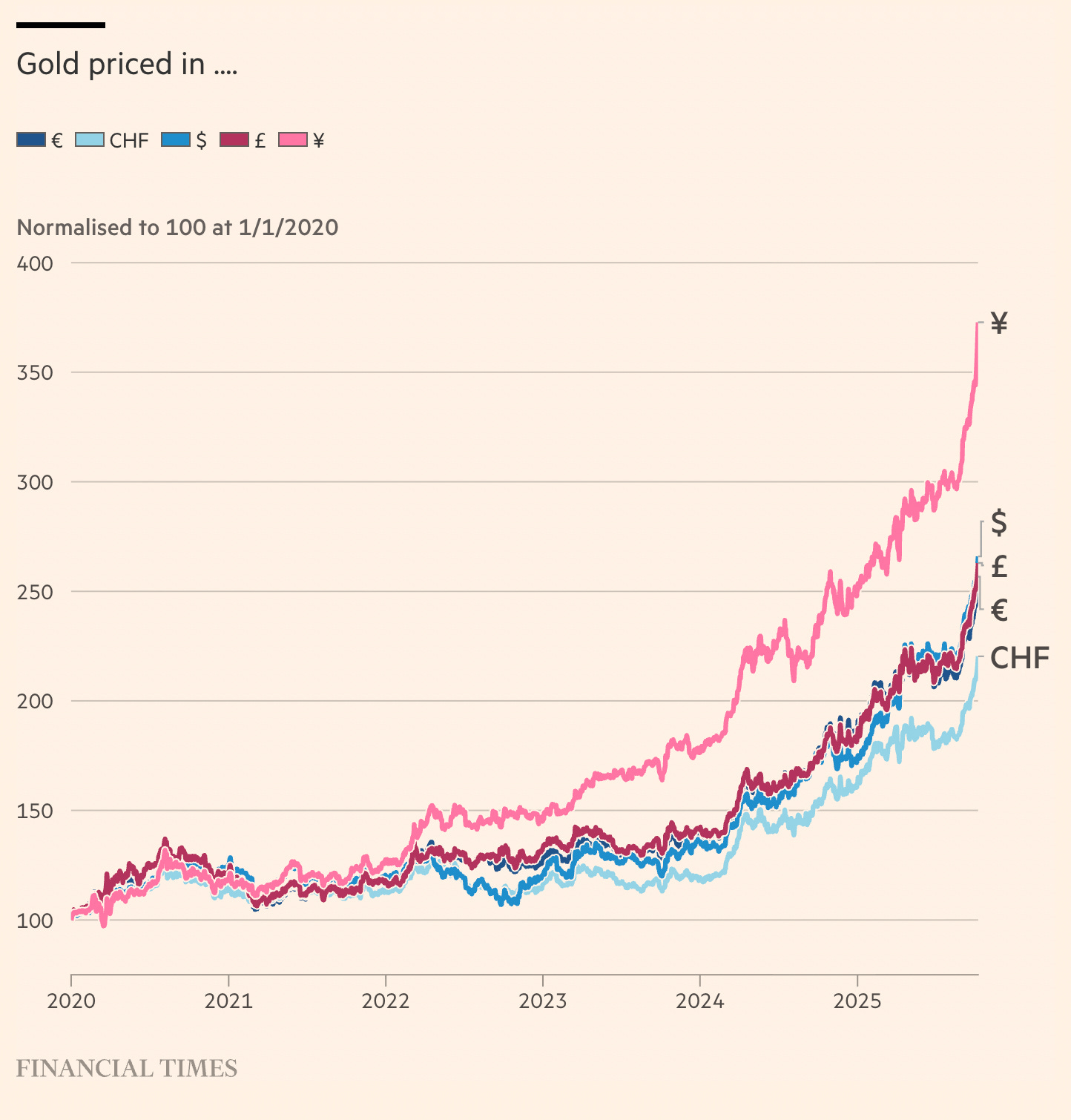

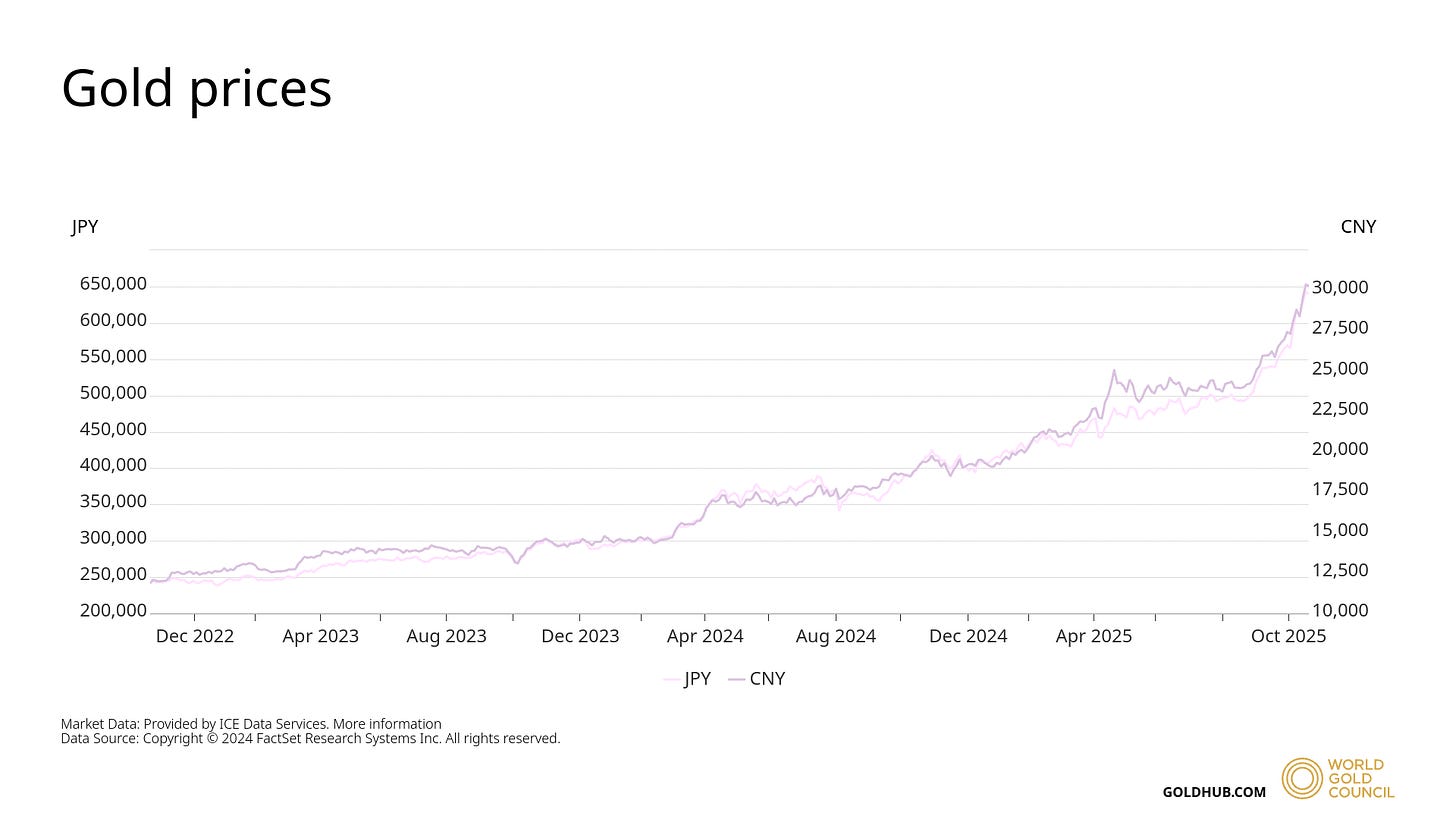

To finish with a precise example that captures these trends, both general and specific: gold. As these charts, it is another clear way that people in Japan - and elsewhere - appear to be voting. Per the prior note, it is worth considering whether this is another indicator of what is starting to take shape.