Enframing in the East

To orient

Staying with China as a ‘manufacturing superpower’, thinking through what it means for energy and consumption. A few more to go, thanks for your patience. Previous notes in the series: one, two, three, four, five.

Two images from my recent trip that capture the contradictions and complexities of the contemporary in China:

Sitting in traffic in rural Sichuan. The car ahead is a new electric vehicle (EV), produced by a Chinese brand I do not immediately recognise, likely charged by hydroelectricity. The driver’s window rolls down, an empty plastic bottle is thrown out the window. It will take more than EVs to save the planet, that’s for sure.

Walking around Erhai in Dali, I notice numerous women wearing full face masks that protect their skin from the strong sun, while allowing them to avoid putting on makeup. Beauty expectations, climate adaptation, and consumption all wrapped in one.

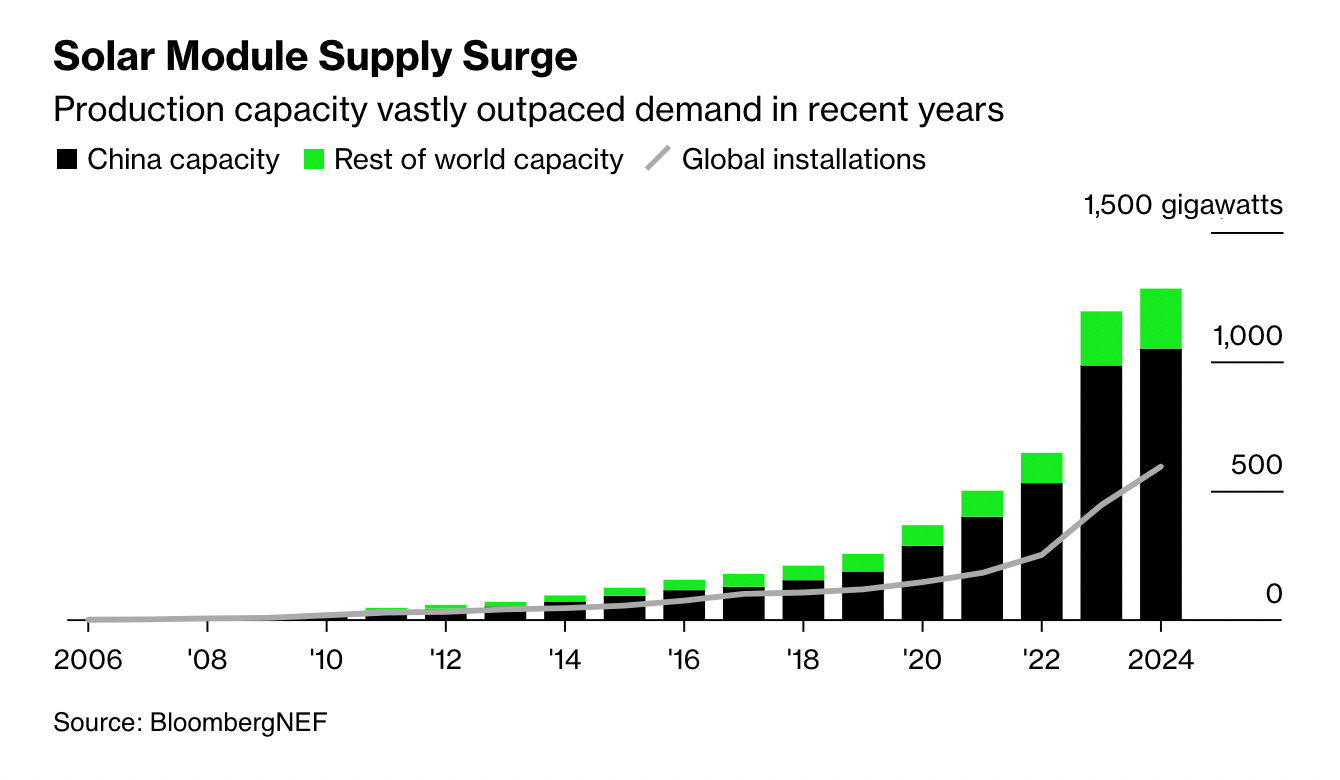

The prior note reflected on Adam Tooze’s suggestion that the, ‘Chinese manufacturing boom just seems to be gathering pace’. The context in which he is making this intervention is China’s central - perhaps determinative - role in the future of climate emissions. It is the country’s unrivalled manufacturing capacity - causing so many economic concerns - that also offers ‘the hockey stick of hope’, the remarkable roll out of solar. This transformation was captured in a recent special issue of The Economist, which judged: ‘the exponential growth of solar power will change the world’. David Wallace-Wells offers an example of what this looks like: ‘In Pakistan, so much rooftop solar was recently imported from China in just six months that the country increased its electricity capacity by 30 percent — without anyone really noticing.’ Indeed, according to the latest BloombergNEF market report, global installations are up 33% on 2023.

China’s overcapacity has allowed it to hit its 2030 renewable energy target six years early, and push the price of solar panels to record lows, which is encouraging demand but causing considerable pain for its producers.

The dulling frame of ‘Cold War 2’ means the US, the EU, even Canada cannot simply take this as a win, instead putting tariffs on solar. One of the few bright spots in terms of dealing with climate change, and Western leaders lack the capacity to adjust and accept it if China is effectively helping to subsidise the global energy transition. While there might be arguments for reshoring solar given increasing geopolitical risks and decreasing costs of production, it is difficult to see how much scope there is for catching up to China in the solar space, and if it is even worthwhile trying, given competing policy concerns and climate demands.

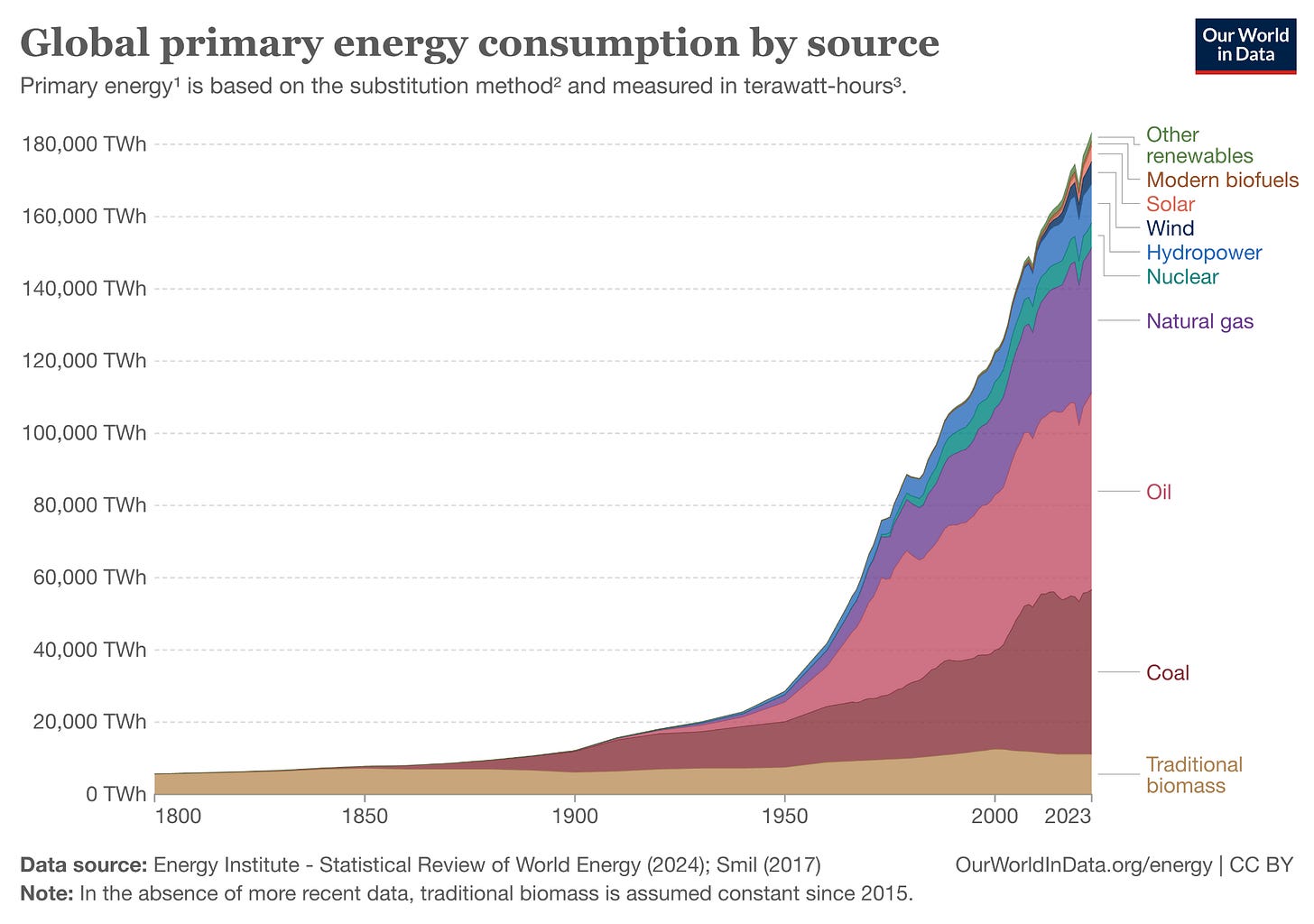

For those focused on the remarkable decline in the cost of solar, the question becomes: ‘what will we do with our free power?’ Presumably the same thing we have always done: consume more. It is here we reach Jevons paradox, whereby technological advances in efficiency end up fuelling increases in demand. Len Brookes explains:

Jevons is very simple. When we talk about increasing energy efficiency, what we’re really talking about is increasing the productivity of energy. And, if you increase the productivity of anything, you have the effect of reducing its implicit price, because you get more return for the same money—which means the demand goes up.

This dynamic is something that Nate Hagens emphasises in his Great Simplification podcast. With each new energy source we have increased the amount of energy being consumed, this is no different with renewables. We just keep adding to our collective energy portfolio and total consumption.

Staying with China’s remarkable achievements in green tech, companies like BYD and Geely now have EVs on market starting around $10,000. What this portends is more cars, more drivers, more roads, more congestion, and with all that, more consumption. Returning to Ivan Illich’s provocative essay from 1973, Energy and Equity:

The widespread belief that clean and abundant energy is the panacea for social ills is due to a political fallacy, according to which equity and energy consumption can be indefinitely correlated, at least under some ideal political conditions.…

Even if non-polluting power were feasible and abundant, the use of energy on a massive scale acts on society like a drug that is physically harmless but psychically enslaving.

He advocated for life to occur at the speed of the bicycle, judging:

High speed is the critical factor which makes transportation socially destructive. A true choice among political systems and of desirable social relations is possible only where speed is restrained.

Illich’s vision is now as quaint as Don Quixote’s knight-errantry. Instead, there has been a constant and steady advance of technology that increases our capacity to control and shape the world, green tech is no different here.

In ‘The Question Concerning Technology’, Martin Heidegger spoke of a logic of ‘enframing’, in which nature becomes ‘standing reserve’. It is noteworthy that he explicitly employed examples of humans using and transforming nature into energy:

In the context of the interlocking processes pertaining to the orderly disposition of electrical energy, even the Rhine itself appears to be something at our command. The hydroelectric plant is not built into the Rhine River as was the old wooden bridge that joined bank with bank for hundreds of years. Rather, the river is dammed up into the power plant. What the river is now, namely, a water-power supplier, derives from the essence of the power station. In order that we may even remotely consider the monstrousness that reigns here, let us ponder for a moment the contrast that is spoken by the two titles: “The Rhine,” as dammed up into the power works, and “The Rhine,” as uttered by the art work, in Hölderlin's hymn by that name.

Recall that China constructed the world’s largest hydropower dam, Three Gorges Dam, the mass of which is so great as to slow the Earth’s rotation by 0.06 microseconds. What this makes clear is geoengineering is not a future prospect, but something we have been doing for quite some time.

China as manufacturing superpower stands at the peak of the intersection of technology and modernisation. It gives a certain slant on the ‘hockey stick of hope’ that the country’s productive capacity makes possible. ‘Fast, cheap, and out of control’ is how the ultra-fashion brand of Shein has been described, but the depiction could also be applied to the remarkable buildout of China’s solar industry. The logic and execution are similar. The ‘ordering principle’ suggests a world more Shein than green.

There is a risk of assigning greater intentionality to this manufacturing leviathan than might be justified. What is on offer is more solar, more wind, more EVs, more green tech, as well as more ICE vehicles, more cranes, more ships, more flip flops, more of anything and everything we might want to order. China produces around 80% of the world’s solar, it also produces around 80% of the world’s sex toys.

When looking at the remarkable growth in solar, EVs and the like, it is tempting to take China’s promotion of ‘new productive forces’ at face value. Yet the scope of its capacity to produce appears far greater and less focused. This is certainly what it feels like on the ground. And so, Chinese engineers are hard at work developing AI technologies, including building new generations of sex toys that are AI-enhanced. Coinciding with the spring Beijing auto show, which displayed China’s remarkable advances with EVs, in Shanghai there was a sex toy expo, with all the latest models too. China will build it all.

Tooze likes to quote the line from Keynes:

Anything we can actually do we can afford.

To which can be added:

Anything we can imagine China can manufacture.

Circling back, a fitting place to finish is with Yuk Hui’s, The Question Concerning Technology in China:

Let us take the example of Latour’s ‘Resetting Modernity’ project. We can understand ‘resetting modernity’ by way of a metaphor that Latour himself employs:

‘What do you do when you are dis-oriented—for instance, when the digital compass of your mobile phone goes wild? You reset it. You might be in a state of mild panic because you have lost your bearings, but still you have to take your time and follow the instruction to recalibrate the compass and let it be reset.’

The problem with this metaphor is that modernity is not a malfunctioning machine, but rather one that works too well according to the logic embedded in it. Once it is reset, it will restart with the same premises and the same procedure. There is no way in which we can hope that modernity can be reset like pressing a button—or rather, this kairos of the modern may be possible for Europe, although I doubt it, but it certainly will not function like this outside of Europe, as I have tried to show by recounting the failures of China and Japan to overcome modernity: the former ended up amplifying modernity, the latter with fanaticism and war. ‘Disorientation’ does not mean simply that one has lost one's way and doesn't know which direction to choose; it also means the incompatibility of temporalities, of histories, of metaphysics: it is rather a ‘dis-orient-ation’.