The ordering principle

To orient

Zooming in and zooming out, continuing to think through and with China. This note moves to the macro, considering consumption and production, and the offer of an international order based on ordering. More charts and less literary references ahead. Previous notes in the series: one, two, three, four.

In terms of our troubles with comprehending the contemporary, one of the big challenges is the combination of speed and scale. This certainly applies in reckoning with China’s emergence and growth. We simply have never had a country exist of such size - containing around 18% of the world’s population - and with such technological capacity. To offer one example, Hannah Richie confirms the data point that, ‘China consumes as much cement every two years as the US did over the 20th century.’

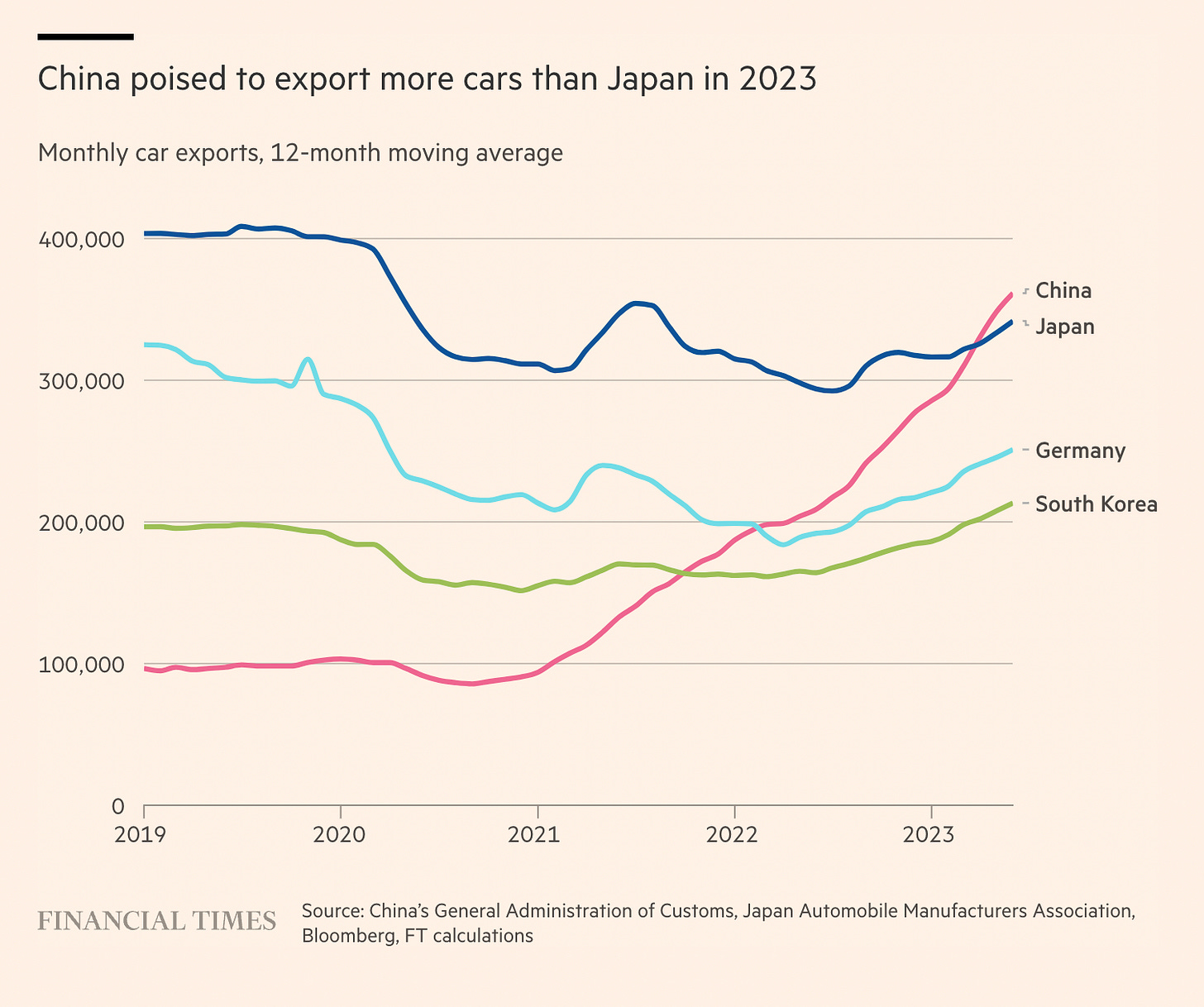

Unsurprisingly, China has come to be the leading producer of cement, as with so many other industries. As has been widely reported, it is no longer just the big and basic stuff that China is increasingly dominant in. The FT has described China becoming the world’s biggest car exporter as a ‘watershed moment’, all the more noteworthy because of the speed at which this change has occurred.

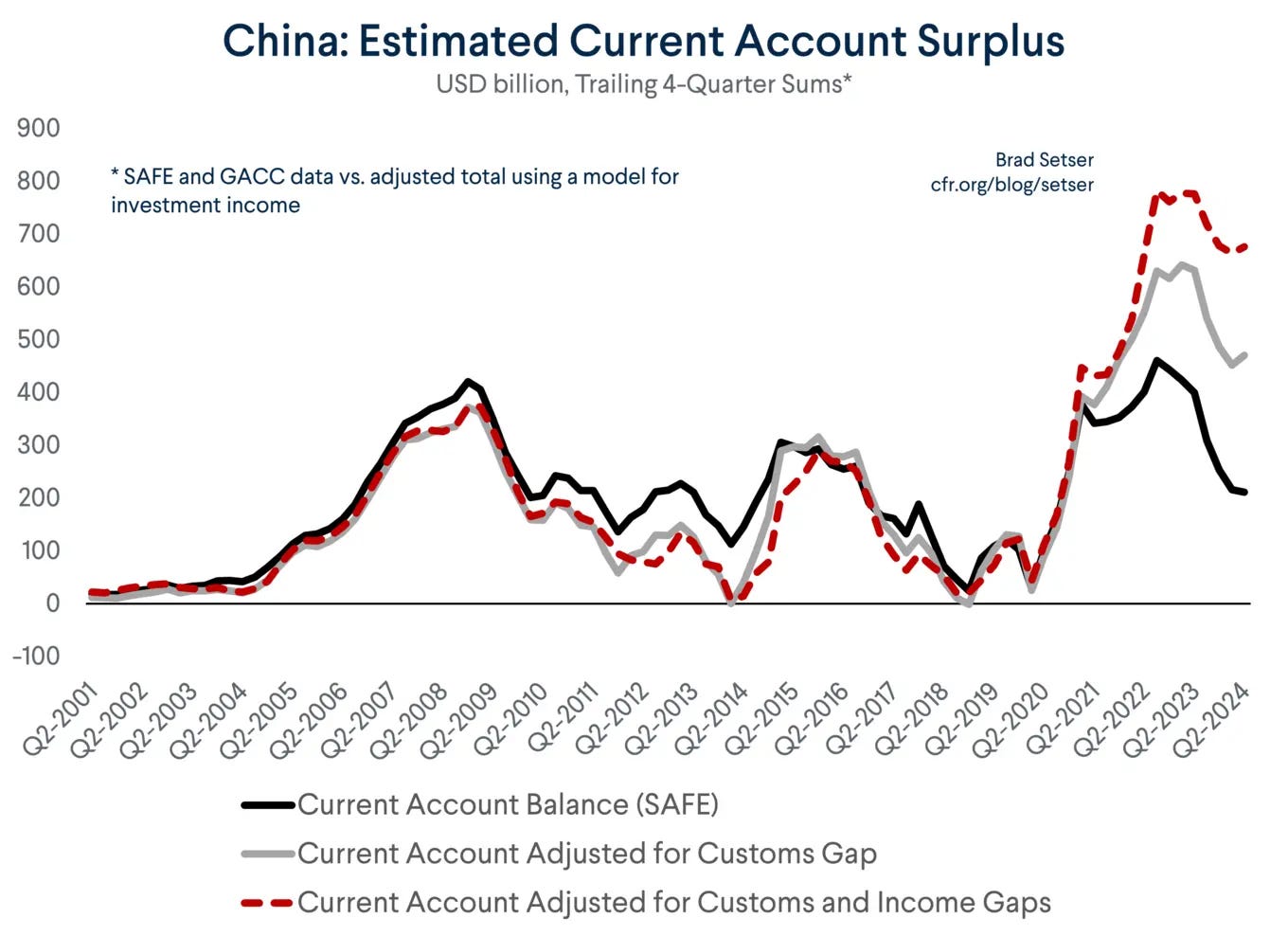

The fate of the automotive industry has become bundled up with a wider set of concerns around Chinese overcapacity and its growing account surplus. According to Brad Setser’s work, the impact is even greater than what reported data would suggest:

The aim of this note is not to directly talk about overcapacity, imbalances, tariffs, and so on. Better leaving that to Michael Pettis, Mathew Klein and co. Rather, it is to try to think through these developments, and what they might suggest about the ‘trap the world has become’. Listening to Kaiser Kuo’s recent Sinica podcast with Adam Tooze, I was struck by a statement Tooze made at the WEF meeting in Dalian:

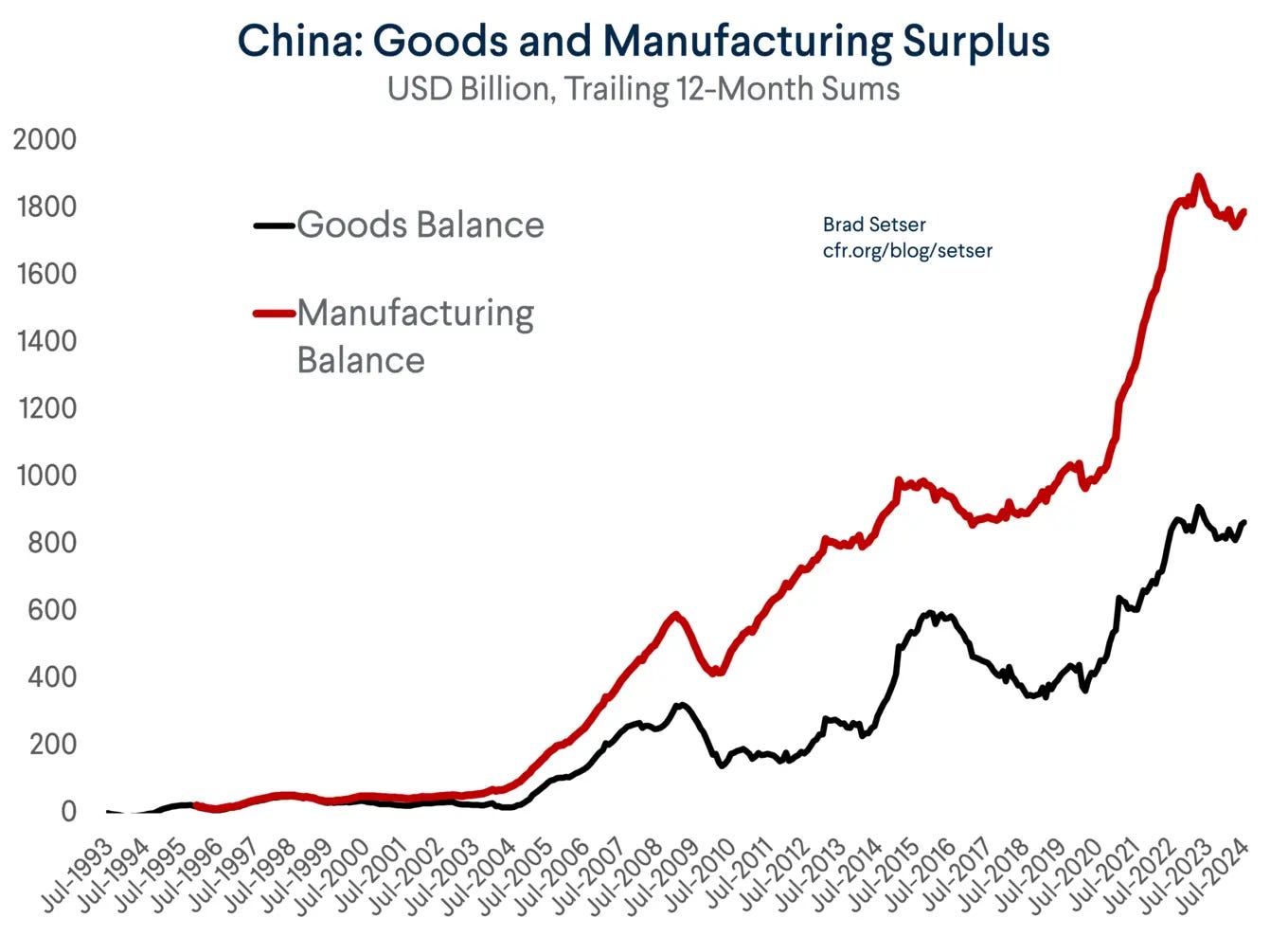

At the aggregate level, the Chinese manufacturing boom just seems to be gathering pace. We have not actually seen what it looks like yet when the Chinese manufacturing miracle really hits its stride.

As the song goes: ‘you ain’t seen nothing yet’. Counter to predictions of ‘the rise and coming fall of Chinese manufacturing’, perhaps the country is only starting to hit its stride, in which its accumulated advantages begin to really kick in. Given the stresses so far, this is a point worth lingering on. Consider this in reference to Richard Baldwin’s suggestion that:

The US is the world’s sole military superpower. It spends more on its military than the ten next highest spending countries combined. China is now the world’s sole manufacturing superpower. Its production exceeds that of the nine next largest manufacturers combined.

Concerns about Chinese overcapacity and exporting its way to economic growth have primarily been framed in reference to strategic sectors and green tech, notably electric vehicles, batteries, solar and other renewable energies. This is another example of how viewing the world through the narrowing concerns of ‘the West’ restricts our understanding. In this case, it actually underestimates the scope of the challenge, insofar as China as a manufacturing superpower entails it producing more of anything and everything. Boiled down, the offer is one of ‘we produce and you consume’. The logic of comparative advantage is not going to work when there is no comparison, in which one side - due to scale and scope - has all the advantage. As Sébastien Jean, Ariell Reshef, Gianluca Santoni & Vincent Vicard detail in their policy brief on ‘the China conundrum’:

Defining product-level dominant positions as a share of more than 50% of worldwide exports, we show that China held a dominant position in almost 600 products out of some 5,000 in 2019. This is at least six times greater than the equivalent number for the United States, Japan or any other country, and twice the number for the European Union considered as a whole. This large number of dominant positions held by China is atypical by historical standards, at least since the 1970s.

These dynamics are challenging not only for developed economies that risk further deindustrialisation, but also for developing countries seeking to increase capacity and marketshare. It is arguably a greater issue for the latter, as they have less scope for action. The compliment to the ‘China shock’ might be the ‘China block’.

Camille Boullenois and Charles Austin Jordan suggest as much in a recent report for Rhodium Group, ‘How China’s Overcapacity Holds Back Emerging Economies’:

While growing Chinese exports benefit developing countries to some extent by providing inputs for their local industries, they also contribute to China’s rising market power, creating new vulnerabilities for the developing world. It has long been assumed that China’s rise up the value chain would create a growing market for labor-intensive manufactured goods from other emerging markets. These hopes will be dashed if Beijing cannot restart the engines of its own domestic growth and absorb more of what it currently exports. Unless Beijing implements serious demand reforms, developing nations will be crowded out of manufacturing by Chinese overcapacity, leaving them dependent and without export opportunities.

On this theme, Andrew Bateson proposes that concerns over geopolitical rivalry and industrial capacity result in an unwillingness to cede ground: ‘Rather than allowing China’s low-end industries to shift to other, lower-income countries, and then importing those products, the idea is to maintain the ability to produce the full range of goods within China.’ This arrangement might suit some in China, it is unclear how well it fits with the rest of the world. Bateson concludes:

China these days is trying to knit together a coalition of other developing countries also opposed to US dominance of the global system. But its official economic theory does not offer much of a basis for what it likes to call “win-win” ties with other developing countries.

Indeed, Zongyuan Zoe Liu argues that the perpetuation of the current dynamic also creates problems for China:

Simply put, in many crucial economic sectors, China is producing far more output than it, or foreign markets, can sustainably absorb. As a result, the Chinese economy runs the risk of getting caught in a doom loop of falling prices, insolvency, factory closures, and, ultimately, job losses.

She further judges that, ‘the Chinese economy clearly needs to strike a new balance between investment and consumption’. Whether and how this occurs will be deeply consequential. If Tooze is right - that China’s manufacturing boom is just getting going - the question of how to make this compatible with the rest of the world will remain one of the defining issues of the present.

In many ways, the challenge posed by China’s production prowess stems from it being the logical extension - perhaps conclusion - of our relentless prioritisation of consumption and convenience. It delivers ‘the goods life’. Given this, it is hardly surprising that what is now on offer is an international order based on ordering. ‘The end of history’ shorn of liberalism: consumption mediated through smartphones, and not much more, indeed, a ‘sad time’, to quote Fukuyama. What type of future does it portend? This should be an open question, but it is invariably rhetorical: we know, we have known for quite some time, but we choose not to know. Recalling Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man, first published in 1964:

The union of growing productivity and growing destruction; the brinkmanship of annihilation; the surrender of thought, hope, and fear to the decisions of the powers that be; the preservation of misery in the face of unprecedented wealth constitute the most impartial indictment — even if they are not the raison d'etre of this society but only its by-product: its sweeping rationality, which propels efficiency and growth, is itself irrational.

The fact that the vast majority of the population accepts, and is made to accept, this society does not render it less irrational and less reprehensible. The distinction between true and false consciousness, real and immediate interest still is meaningful. But this distinction itself must be validated.