Turning, returning to Fukushima

3.11

Breakdown and failure reveal the true nature of things. In failure, life’s reality is not lost; on the contrary, here it makes itself wholly and decisively felt.

Karl Jaspers, Tragedy is Not Enough (1952)

As shocks and surprises mount up, in time so do the anniversaries. Another year passes since a disaster was visited on a people and a place. Today is one of those days. On 11 March 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake struck the Tohoku region, triggering a massive tsunami and nuclear accident at Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

Despite Japan’s long history with earthquakes and tsunamis, and it being regarded as a world leader in disaster preparation, the country was simply not ready for what happened. To quote former Prime Minister Kan: ‘the cause of this catastrophe is, of course, the earthquake and the tsunami but, additionally, the fact that we were not prepared. We did not anticipate such a huge natural disaster could happen’. And yet it did. While the death toll of approximately 20,000 people was overwhelmingly from the tsunami, it is the nuclear accident that captured much of the world’s attention.

It was in Fukushima where the second worst nuclear accident in history occurred. An unexpected - but not inconceivable - natural occurrence interacted with ageing technology, degraded regulatory institutions, misaligned economic incentives, and a denial of externalities. Bad luck and bad practice resulted in a very bad outcome.

What is often forgotten is that the Onagawa nuclear power plant, which was the closest to the epicentre of the earthquake, survived intact without incident. This can be seen in the above map, care of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. It was not inevitable that the natural hazard would cause the technological accident, there were people and organisations responsible for decisions and structures that resulted in the disaster that unfolded. In this sense, the Fukushima nuclear accident sits alongside the Iraq War and the Global Financial Crisis: accountability without responsibility. Actors and institutions were at fault, but nothing happened.

The immediate, activated response focused on the dangers and follies of nuclear power. This is deeply understandable, the shabbiness of Japan’s ‘nuclear village’ was rightly revealed and reviled. It is hard to offer a charitable reading of TEPCO in this disaster. And yet, with time, the consequences and meanings that Fukushima has taken on and manifest in the world are for more ambivalent and ambiguous.

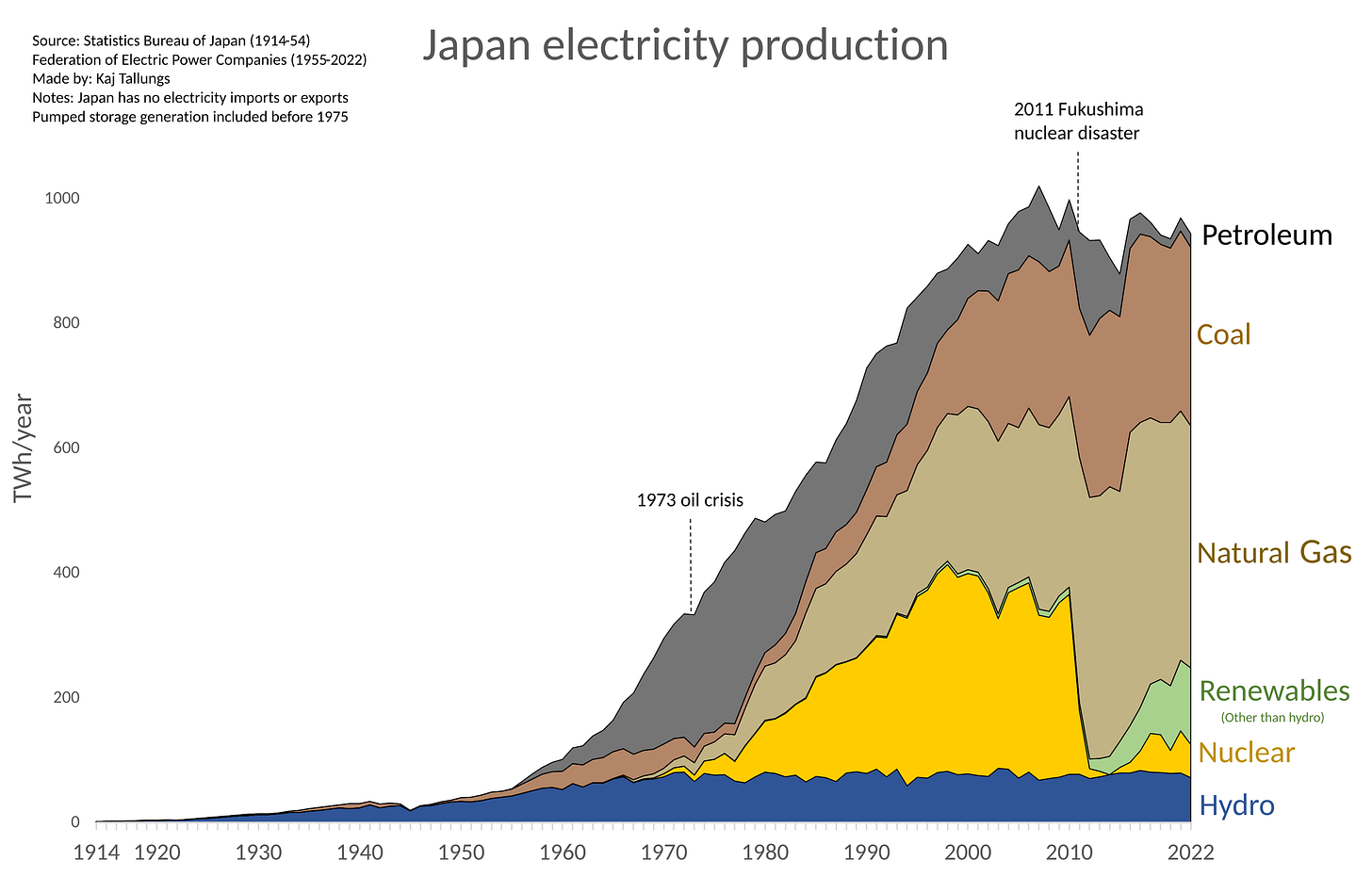

The problems of ‘energy blindness’ means that not only are energy needs and inputs rarely recognised or thought about, the necessary tradeoffs and risks are also overlooked. The demand for energy overwhelms other concerns, again and again. For Japan, reactors were turned off, but the energy demand did not disappear, it was simply displaced. Less nuclear meant more coal and gas, and with it, more emissions.

The Fukushima accident strengthened longstanding fears about the viability and safety of nuclear power. For many, avoiding the low probability / high impact event of a nuclear accident became more important than the role of nuclear in reducing carbon emissions and trying to forestall climate change becoming a high likelihood / high impact outcome. As a result, there was a reduction in the use of a low-carbon energy source during a period in which carbon emissions became consistently more consequential. There appears to be greater interest now in expanding nuclear power, but it is unclear how viable it is and on what timelines it would be possible.

Consider James Hansen’s reflections from December 2024:

Development of cheap renewable energies is useful, but not a panacea – it will not cause fossil fuels to go away any more than fossil fuels caused wood burning to go away. We are still burning as much wood and biomass as at any time in history. At long last, in just the past couple of years, the United Nations says, “oh, we need the help of nuclear power, we should triple nuclear power.” Well, alas, that is easier said than done. It takes time. Renewables had several decades of unlimited subsidy via renewable portfolio standards. Why did we not, instead, have clean energy portfolio standards? Here, we scientists should accept part of the blame. We were well aware that nuclear power has the smallest environmental footprint of the major energies and even old technology nuclear power saved millions of lives. Nuclear power also has the potential to be inexpensive. But we were too passive, perhaps because we knew that we would be criticized because of unfounded fear and disinformation about nuclear power spread by a gullible media.

One can hardly accuse Hansen of not being aware of the costs and consequences of our constant demand of ‘more and more and more’ energy. Rather, there is a keen appreciation that we are well past the time when we might have had the luxury of a wider menu of options. In a world in which there remains a tight correlation between energy use and economic wellbeing, nuclear offers certain benefits and risks. There are no magic bullets or cost-free solutions, there are only different tradeoffs. This is something I only came to understand properly after the triple disasters.

It would be easy to keep presenting charts and considering the expected and unexpected consequences of the disaster. There is much more that could be said. But let us return our focus to Fukushima and Tohoku. Nobody could argue in good faith that the region is better off now. It is not. The landscape still bears the scars of what happened.

Disasters represent ruptures in society, literally and figuratively. Things break, places and people too. Talk of ‘building back better’ is preferred, as it papers over the uncomfortable truth, namely, that some things cannot be rebuilt. Moreover, shocks and disasters tend to amplify and exacerbate existing vulnerabilities. Before the triple disasters, the region was struggling with issues related to an ageing and shrinking population, as well as limited economic opportunities. These challenges have only been reinforced, all the money the Japanese government has thrown at the region has been insufficient to address these deep-seated issues.

On completing a research project on Fukushima around 2015 or so, the conclusion I reached was:

Fukushima tragically teaches us the need to reckon with the fragility of things and people, to acknowledge the role of the unexpected and unlikely, to deal with the shortcomings of institutions and systems, and to recognise that some things cannot be undone. This, in turn, should foster an ethos of humility. A sense of care. An appreciation of what was lost. A desire to conserve. A capacity to move forward.

I continue to hold onto a keen sense of what happens when things break: what is lost, who is impacted, the costs and consequences. Over the years, however, the more I have visited Fukushima, the more aware I have become of how the region has slowly dealt with what happened. Unevenly and imperfectly, life has moved on. It does because it must. To invoke Paul Valéry via Hayao Miyazaki:

The wind is rising! . . . We must try to live!