Since we possess the power of total destruction, but not yet the power of controlling it with calculating certainty, everyone asks:

What can be done? Where is the way out?

This was Karl Jaspers considering the ‘new fact’ of atomic weapons in his 1958 book, The Atomic Bomb and the Future of Man. As the ‘new fact’ became old, and the Cold War finished with a whimper and not a bang, the nuclear threat faded from our collective view. At some point, most of us stopped asking these questions that so concerned Jaspers. Yet the problem never disappeared.

Another thinker who emphasised the significance of nuclear weapons was Günther Anders, who concluded that our world was irrevocably altered on 6 August 1945, when the first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. On that terrible day humanity introduced ‘the possibility of our self-extinction’. He suggested we are collectively mute, blind and deaf to the danger of nuclear weapons. In his 1959 paper, ‘Theses for the Atomic Age’, which is a remarkable precursor to much of Ulrich Beck’s theorising of risk society, Anders captured the difficulty of fully comprehending the destructive possibilities of nuclear weapons, and what that danger means for our world:

Not only has imagination ceased to live up to production, but feeling has ceased to live up to responsibility. It may still be possible to imagine or to repent the murdering of one fellow man, or even to shoulder responsibility for it; but to picture the liquidation of one hundred thousand fellow men definitely surpasses our power of imagination. The greater the possible effect of our actions, the less are we able to visualize it, to repent of it or to feel responsible for it; the wider the gap, the weaker the brake-mechanism.

Through my teaching and research, I have tried to better recognise the reality of the nuclear threat. It is hard. It is much easier leaving it in the background. Yet as events of this year have reminded us, background can become foreground very quickly.

In considering the current conflict, Nina Tannenwald warns that ‘there is a whiff of nuclear forgetting in the air’, a failure to fully appreciate the very real danger that exists with escalation. She outlines the situation succinctly:

As a result of Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine and Russian officials’ alarming nuclear threats, the world is closer to the use of nuclear weapons out of desperation—or by accident or miscalculation—than at any time since the early 1980s.

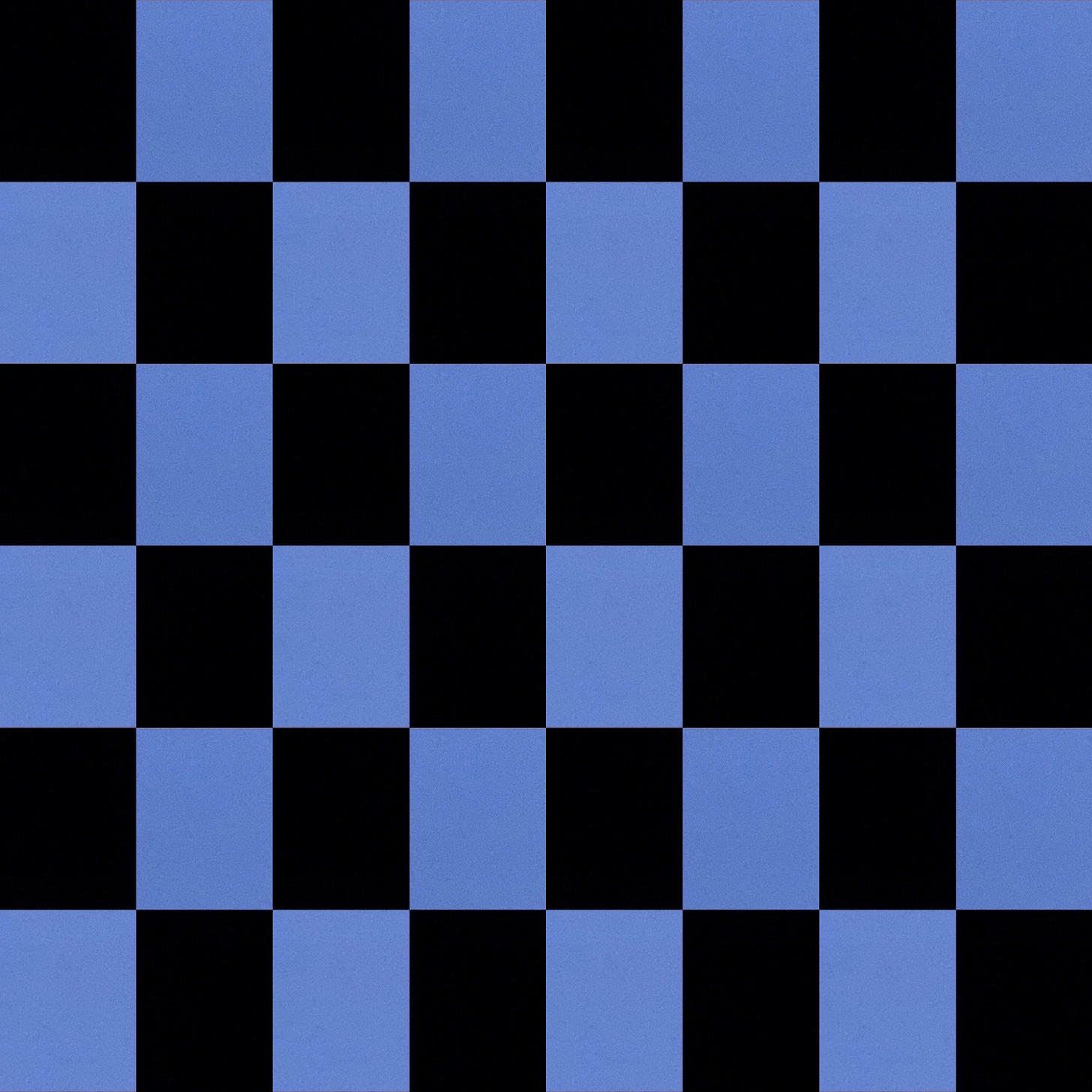

As with so many other components of the contemporary polycrisis, we are dealing with a problem unresolved, a resolution deferred. We are still left with what Anders termed, ‘Hiroshima as a world condition’. Certainly, the danger has been tempered with a reduction of the total number of nuclear warheads, as this chart by the Federation of American Scientists demonstrates:

Yet the chart also captures Anders’ basic point: it might give some colour and scale to the problem we are discussing, but it cannot capture the absurdity of our reality, a situation in which there still remains so much destructive power.

Regardless of safety measures and precautions, the basic dilemma is there is little margin for error. To this must be added the possibility for accidents and mistakes, which is detailed in Eric Schlosser’s excellent book and accompanying documentary. All that is required for a very bad outcome is one misjudgement, one miscalculation, one mistake, one misfortune.

JFK did not need the Cuban Missile Crisis to comprehend the dangers of a nuclear world, a year before he told the United Nations:

Every man, woman and child lives under a nuclear sword of Damocles, hanging by the slenderest of threads, capable of being cut at any moment by accident or miscalculation or by madness.

The sword and thread never disappeared. We just stopped looking up.

There is something remarkably grotesque about nuclear weapons. Not only that such destructive power exists, but that it is held by fellow humans, flawed and imperfect, liable to incentives and emotions, poor sleep and bad moods, such minor failings that could be amplified with such extreme consequences in the wrong sequence of events. Perhaps it will all be fine, but if not, well, then what?

These concerns were present in Robert S. McNamara’s thinking, which was greatly shaped by the experience of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Reflecting in the 1990s, he wrote:

The point I wish to emphasize is this: human beings are fallible. We all make mistakes. In our daily lives, they are costly but we try to learn from them. In conventional war, they cost lives, sometimes thousands of lives. But if mistakes were to affect decisions relating to the use of nuclear forces, they would result in the destruction of whole societies. Thus, the indefinite combination of human fallibility and nuclear weapons carries a high risk of a potential catastrophe.

For nuclear weapons to be safe, we need perfection. And that is what we lack.

To return to Jaspers’ questions - ‘What can be done? Where is the way out?’ - he suggested that as a starting point, ‘what needs increasing is the fear of the people; this should grow to overpowering force, not of blind submissiveness, but of a bright, transforming ethos’. Likewise, Anders determined that, ‘it is our capacity to fear which is too small and which does not correspond to the magnitude of today’s danger.’ Both thinkers called for a fear that would generate thought and action, that would look up to see the sword and the thread.

Admittedly, generating the right kind of fear is not easy, as recent efforts around climate change have demonstrated. It has proven difficult to warn of catastrophe without bludgeoning people into states of passiveness, cynicism, disbelief, or generating such concern that it leads to an inability to weigh up competing demands and priorities. Yet it should be possible. Indeed, perhaps this must be part of the response to polycrisis: fear; a creative, productive form of fear, one that consciously and actively reckons with the scope of the problem, that motivates thought and action.

For more on the thought of Günther Anders, check my conversation with Elke Schwarz, which was framed around his thinking.