I’m planning another note in the impromptu series on Japan, this one is more academic, presenting a paper I’ve written on Gramsci’s over-used line about ‘interregnum’.

From kinetic conflicts, geopolitical rivalry, economic imbalances, societal polarisation, energy transitions, environmental destruction, technological transformations and much more, evidence of an order breaking is easy to find. In speeches and reports, magazines and academic journals, trade books and scholarly tomes, all the way through to social media posts and AI-generated slop, one can find a litany of descriptions of the world as being in an ‘interregnum’. One might posit that such judgements have become ‘common sense’.

Originally a legal term to describe a discrete period between rulers, to invoke ‘interregnum’ now is to bring forth the ghost of Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist who haunts the contemporary. His once obscure notebooks written while imprisoned by the Fascists have become remarkably influential over the last half century. In recent years, there has been a constant turning to a specific entry, and a specific line: ‘the old is dying and the new cannot be born’.

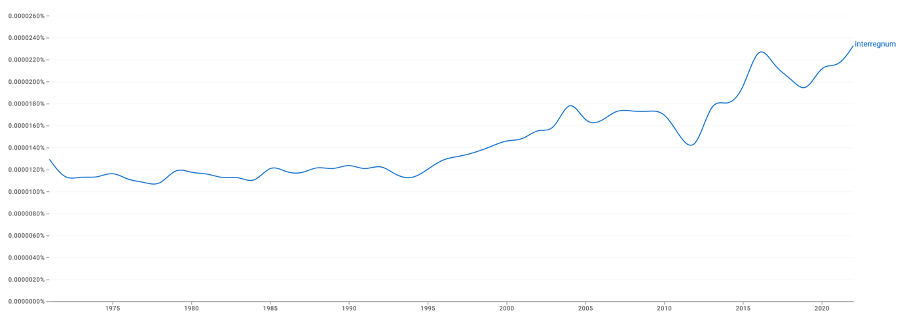

According to Google Ngram Viewer, there has been a steady increase in ‘interregnum’ being used since 2012, peaking in 2016, followed by a shallow decline, and reaching new highs in usage in the 2020s. Through until the 1980s and 1990s, when the term was used it was generally the narrow legal meaning that was meant. Since then, however, it is overwhelmingly used in reference to Gramsci.

A bit over a year ago, I spent some time digging into this trend, drafting a chapter on Gramsci’s entry on interregnum, sketching its unlikely trajectory and considering what it suggests for understanding the present. I published part of it in a previous note. In the period since, however, I’ve determined it won’t appear in the book I am working on, so I thought it was worth making it more widely available. I’ve revised it slightly to now include Adam Tooze’s intervention on the theme from late last year. Hopefully the paper will be of interest to some. It offers a genealogical sketch, putting Gramsci’s current over-use in context, and reflecting on how invoking interregnum can both assist and impede thought.

This is my first attempt at posting a manuscript on SocArXiv.org, an open archive for the social sciences. More on the logic behind that in another note to come. The full paper is available here:

Christopher Hobson, ‘Memes and monsters of the interregnum: Gramsci between the times’, Manuscript, 2025. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/gzhrq_v1

Abstract

Faced with a continually mounting array of shocks, surprises and shifts, there is an understandable search for frames to describe these confusing conditions. A combination of the collapse of previous certainties with the lack of a new paradigm solidifying has led many to depict the present moment as an interregnum. This is not a neutral term, to use it is to bring forth the poetic phrasing of Antonio Gramsci: ‘the old is dying and the new cannot be born’. Through a genealogical engagement with Gramsci’s prison notebook entry, this paper traces the remarkable trajectory of the term from obscurity to being adopted by commentators across the political spectrum. The paper considers Gramsci’s original prison notebook entry, observes the lack of engagement with it during the 1960s and 70s when other parts of his work were picked up. Indeed, it was only following the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, and the entry being coterminously invoked by two influential scholars, Zygmunt Bauman and Slavoj Žižek. The paper examines how Bauman and Žižek each offered a template for how interregnum has been used in the years since. In the first mode, as represented by Bauman, Gramsci’s entry is placed at the beginning of the analysis and then serves as a frame for the subsequent discussion of maladies identified. In the second mode, as found in Žižek, interregnum appears at the end as part of the argument’s grand finale. In both renditions, Gramsci is deployed to buttress already established arguments. The paper surveys some more interesting and provocative engagements with the entry in recent years presented by Carlo Bordoni, Wolfgang Streeck and Adam Tooze. These are an exception to the more common trend of Gramsci’s interregnum being flattened and thinned out, reduced to an analytical meme. Bemoaning the death of the ‘old’ and the rise of ‘monsters’ is much easier than seriously reckoning with the contradictions and difficulties of an expanding empty space, one devoid of historical guarantees or clear precedents.

-

I hope the paper might be of interest / use to some readers. Feel free to read, cite, share, get in touch etc: christopher.hobson@anu.edu.au or info.hobson@gmail.com