In media res, in the style of immediacy

Polycrisis pairings

Apology and explanation: This is the last of the ‘polycrisis pairings’ series (see notes one and two), then a pause. I am keenly aware one of the issues I raise below is the problem of immediacy and yet I am sending these out in a flurry. I also end up using the terms ‘left’ and ‘right’, which I generally try to avoid. Well, now is ‘the time of monsters’ and contradictions…

History does not sustain the choice—really the fantasy—of not being in medias res; neither for theorists nor their ideas.

Uday Singh Mehta, Liberalism and Empire

There’s this other thing, which Draenos brought up…“groundless thinking.” I have a metaphor which is not quite that cruel, and which I have never published but kept for myself. I call it thinking without a banister—in German, Denken ohne Geländer. That is, as you go up and down the stairs you can always hold on to the banister so that you don’t fall down, but we have lost this banister. That is the way I tell it to myself. And this is indeed what I try to do.

Hannah Arendt, Thinking Without a Banister

The aim of this note is to continue thinking alongside Adam Tooze’s work and thinking through the frame of polycrisis, which he has helped to popularise. As he readily acknowledges: ‘Polycrisis is underspecified. It is a weak theory.’ The common response is to dismiss what the term covers either as ‘just history happening’, or to judge that our current theoretical toolkit is sufficient, as Tooze’s New School interlocutors seemed to suggest.

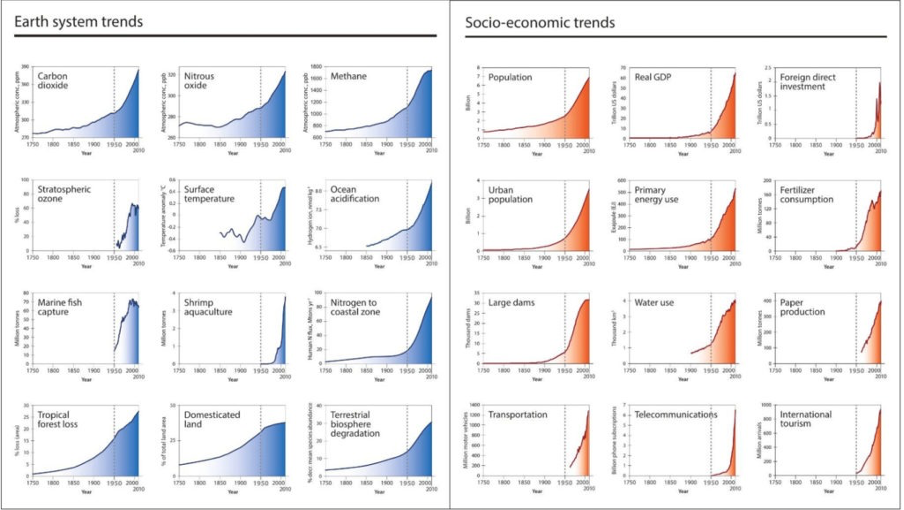

Ultimately there is an analytical wager: how much does ‘the great acceleration’ matter? How different is a world of 8 billion people compared to 1 or 2 billion? How distinct are environmental change and planetary boundaries as a condition?

How different is a world of 5 billion people connected together through the internet, compared to 2 billion connected through telephone, radio and TV, or 1 billion primarily through print? Alongside questions such as these, it must also be asked: how are LLMs and AI challenging and altering the conditions of communicating and knowing? I will return to the role of the digital later in this note, but it is valuable to highlight it, as I am starting to think that the change we are undergoing in terms of communication is almost as momentous as that of climate.

Adopting the polycrisis frame is effectively placing the analytical bet that these developments accumulate into conditions and crises that are different and distinct, that are in some ways novel and that pose new questions. From this, one response is the familiar academic one of trying to conceptualise and study further. The Cascade Institute have been central to attempts to map out polycrisis as a field of research. A 2024 report, ‘Polycrisis Research and Action Roadmap’, identifies gaps and priorities for polycrisis analysis in terms of theoretical foundations, empirical research, practical applications, and community building. In other work, the Cascade team have sought to develop a social scientific conception of polycrisis, setting out causal mechanisms and offering some basic models of crisis interaction and feedbacks. This work has a great clarity to it and is helpful with more carefully thinking through the ways that different crises connect and relate to one other. With these efforts, I do wonder if they lapse into echoing the mistaken hope of climate scientists that if they could just demonstrate that global warming poses a major threat and it is caused by human activity, then change would follow. Nonetheless, this work is valuable and needed.

For those who adopt more of a Ulrich Beck inspired reading of polycrisis, which is invariably much more fuzzy and unsatisfying, there is less confidence in our capacity to comprehend and cleanly make sense of what is unfolding. As Tooze judges, ‘Polycrisis is useful precisely because it reminds us of the knowledge crisis, the gap between inherited critical theory and the radicalism of our present.’ He concludes:

My suggestion is not so much that capitalocentric readings of modernity tend to lead us to underestimate the possibilities for radical agency, but that they tend to lead us to underestimate the scope for catastrophe. A world at loose ends with itself may have more degrees of freedom, but it also has novel and terrifying scope for crisis.

The escalation of the environmental crisis, the emergence of multi-polar great power competition (the escalation of regional conflicts articulated with the tripolar nuclear arms race) and the extraordinary acceleration of oligarchic wealth (Musk) create a novel situation with new catastrophic potential. This catastrophic potential might be thought of as impelled by the violence of “hyper agency”, the magnitude of environmental blowbacks (as witnessed for instance in the form of a pandemic), or the sheer meaningless of public discourse - an attrition that goes beyond ideology, which could, at least, be said to serve an instrumental purpose.

Tooze’s emphasis is on the stakes, and he displays frustration with those who want to continue to think in terms of (narrow) academic debates, seen more directly here:

We need to grow up. There’s too much at stake in the world right now. Things are too urgent. We need to be in the present, as best we can, fully engaged in medias res.

The challenge as I see it, is precisely to centre our thoughts in the present, to be as much in medias res as we possibly can be.

This is in the context of Tooze reflecting on how he has inverted and adopted the criticism of his work being ‘in media res’ levelled by Perry Anderson. What his response points to is the need to better align our analysis with our practice, and for those who judge global conditions to be fraught and time sensitive to more carefully reflect on what are the best ways of acting in and with that knowledge.

One can extend the claim by recalling Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World, in which she makes the argument that Steven Bannon is effectively thinking in media res, but towards very different ends:

Steve Bannon, regardless of whatever else he may be, is first and foremost a strategist. And he has a knack for identifying issues that are the natural territory of his opponents but that they have neglected or betrayed, leaving themselves vulnerable to having parts of their base wooed away….

As Bannon gazes through the one-way glass, he is not only learning what issues his opponents are neglecting and ignoring, and finding fertile new territories to claim as his own, or at least pretend to.

One of the main claims of Klein’s book is that by failing to engage on equivalent terms the left cedes space and ground to what she dubs ‘the Mirror World’. Yes, we could invoke Gramsci here, but the point is not to. Instead, to recall Arendt, when ‘the chips are down’, we must think ‘without a banister’, to operate in media res.

Staying with Klein, another important theme of Doppelganger is how confusing and disorientating the digital world is, how easy it is to get lost in it and through it, how the virtual mediates and distorts the real. Klein’s book is a meditation on how living and being online transposes and shapes offline, the boundary blurs and breaks.

And it is here that it is possible to identify a difficulty with trying to think in media res in these conditions. Put strongly, invoking a nice Latin phrase can be a way of dressing up what is effectively theorising ‘in the style of immediacy’, to invoke Anna Kornbluh’s depiction of the contemporary. One need not accept Kornbluh’s strained attempt to make immediacy a ‘master category’ to appreciate the insight she captures:

The ideology of immediacy holds a kernel of truth: we are fastened to appalling circumstances from which we cannot take distance, neither contemplative nor agential, every single thing a catastrophe riveting our attention.

As Kornbluh details, socio-economic conditions combine with a culture mediated through digital platforms that push us into immediacy, which can further disorientate and dysregulate. Kornbluh argues that:

The world’s proliferating abasements continually render immediacy more seductive and continually inflate its apparent purchase, obscuring immediacy’s own role in immiseration. Immediacy impedes the public, conceptual, and reasoned mediations that are essential to limiting the devastations of deinstitutionalized society, privatization, and ecocide, and crucial for imagining different frames of value, meaning, representation, and collectivity.

Like many claims in the book, I am not fully convinced, but it prompts thought. She points to a challenge: the pitfalls that come with being ‘extremely online’, as much a problem for those on the left as the right. To sharpen the point: in December, a time that normally includes a break around Christmas, and in which Tooze had major surgery, Tooze and his team published 39 posts on Substack (mostly ‘top links’, but still more than 1 per day), along with 3 episodes of his Foreign Policy podcast. And so far in January, 3 substantive Chartbooks and 15 ‘top links’, along with 3 new podcast episodes. One need not be ‘perched in some ivory tower’ to wonder whether it is reasonable to describe all of this as simply being, ‘in media res’.

In Vita Contemplativa: a praise of inactivity, Byung-Chul Han judges:

Without moments of pause or hesitation, acting deteriorates into blind action and reaction.

Yet these are the precisely the conditions that digital platforms encourage and manifest. ‘It is what happens to society when the defenses against information glut have broken down’, Neil Postman’s determined in Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology. He wrote:

When the supply of information is no longer controllable, a general breakdown in psychic tranquillity and social purpose occurs. Without defenses, people have no way of finding meaning in their experiences, lose their capacity to remember, and have difficulty imagining reasonable futures.

A similar rendering has been offered more recently by Byung-Chul Han. In Infocracy: Digitization and the Crisis of Democracy:

Information is relevant only fleetingly. Because it lives off the ‘appeal of surprise’, information lacks temporal stability, and because of its temporal instability, it fragments our perception. It draws reality into a ‘permanent frenzy of actuality’. It is not possible to linger on information. This makes the cognitive system restless.

And in The Crisis of Narration:

The information society is an age of heightened mental tension, because the essence of information is surprise and the stimulus it provides. The tsunami of information means that our perceptual apparatus is permanently stimulated. It can no longer enter into contemplation. The tsunami of information fragments our attention.

Much as sea level rise threatens our coasts, so the tsunami of information threatens to become a permanent deluge as ‘AI slop’ washes over and engulfs what is left of communicating online. Here, of course, another concept arises with a warning: the dawning of the ‘enshittocene’, a time in which ‘enshittification is coming for absolutely everything’, to quote Cory Doctorow. Including meaning and language, at which point, time to invoke Jean Baudrillard as an untimely thinker. His warning in The Gulf War Did Not Take Place:

At a certain speed, the speed of light, you lose even your shadow. At a certain speed, the speed of information, things lose their sense. There is a great risk of announcing (or denouncing) the Apocalypse of real time, when it is precisely at this point that the event volatilises and becomes a black hole from which light no longer escapes. War implodes in real time, history implodes in real time, all communication and all signification implode in real time.

‘At a certain speed, the speed of information, things lose their sense.’ Indeed. We are all in Baudrillard’s world now. At this point, we circle back to polycrisis being partly about a breakdown in our capacity to know. And reflect. And communicate.

Acknowledging these concerns and problems, there remains strong analytical grounds for judging the present moment as a kind of mirror or doppelganger of 1848 or 1989, a pivot on which history may or may not turn. Thus, there are valid and vital reasons for refusing the comfort of the ivory tower, for reckoning with the wrecking, for genuinely and generously thinking in media res. In doing so, however, there is a need to be cognisant of how the tools, structures and platforms through which we are analysing, acting and communicating are bending, warping, breaking.

To finish, a move away from my immediacy, of which this note is also meant as a form of autocritique. From an unpublished chapter I wrote in 2020:

Given this, what can one do at such moments? Insofar as dark times are distinguished by a blurring of truth and non-truth, as well as a fracturing of discourse, to be able to act and to respond one must first be able to see what is happening. Arendt considered the possibility of withdrawing from such a world, but regarded this as ultimately self-defeating and ineffective for ‘the result will always be a loss of humanness along with the forsaking of reality’. While she asked how much reality should be retained to maintain a sense of humanity, the answer was implicit in the way the question was asked: as much as possible. Arendt explained elsewhere that, ‘this means the unpremeditated, attentive facing up to, and resisting of, reality – whatever it may be.’ Arendt determined that such efforts were, ‘guided by their hope of preserving some minimum of humanity in a world grown inhuman while at the same time as far as possible resisting the weird irreality of this worldlessness’. The point is that this becomes difficult and thus meaningful at such moments. Insofar as dark times are attended by the disfiguring of discourse, this degrades the capacity of people to identify and respond to what is happening, as it means a degrading of the tools by which we help to give meaning and understand the world. She observed that, ‘eyes so used to darkness as ours will hardly be able to tell whether their light was the light of a candle or that of a blazing sun.’

Thank you for your engagement and patience. This note is meant as a reflection on my own practice and thought, as well as a prompt for others working on polycrisis. With this done, I’ll be stepping back and pausing these notes for the time being. Presumably back at some point in the next month or so. I’m contactable at: info.hobson@gmail.com or christopher.hobson@anu.edu.au