Fukushima in perspective

The view from 2023

I am not someone who notices anniversaries, and yet, each year as 11 March approaches, my mind returns to Tohoku, and the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear accident that struck the region in 2011. I was in Tokyo at the time, and while I was fortunate enough not to be immediately impacted, the experience and subsequently researching the disasters has had a lasting impact. I have written about it previously, and in a later post I might further reflect on some of the lessons I learned. Here I want to consider consider some of the wider consequences from the vantage point of 2023.

Arguably the most significant impact was effectively a lost decade of nuclear power generation. Or put differently, the reduced use of a low-carbon energy source during a period in which carbon emissions became consistently more consequential. The Fukushima accident strengthened longstanding fears about the viability and safety of nuclear power. For many, avoiding the low probability / high impact event of a nuclear accident became more important than the role of nuclear in reducing carbon emissions and trying to forestall climate change becoming a high likelihood / high impact outcome.

For Japan, turning off most of its nuclear reactors has meant more coal and gas. While the lack of confidence in nuclear in the country is readily understandable and not without cause, its policy response has not been positive either in terms of the country’s carbon emissions or energy security. The conclusion I reached in 2013 has largely held, with Japan’s energy policy occupying an ‘unproductive and suboptimal middle ground’:

The direction Japan is headed – essentially cutting the baby in half – will solve neither the economic nor environmental challenges Japan faces in securing its energy supply, nor will it satisfy the anti-nuclear majority or pro-nuclear business groups.

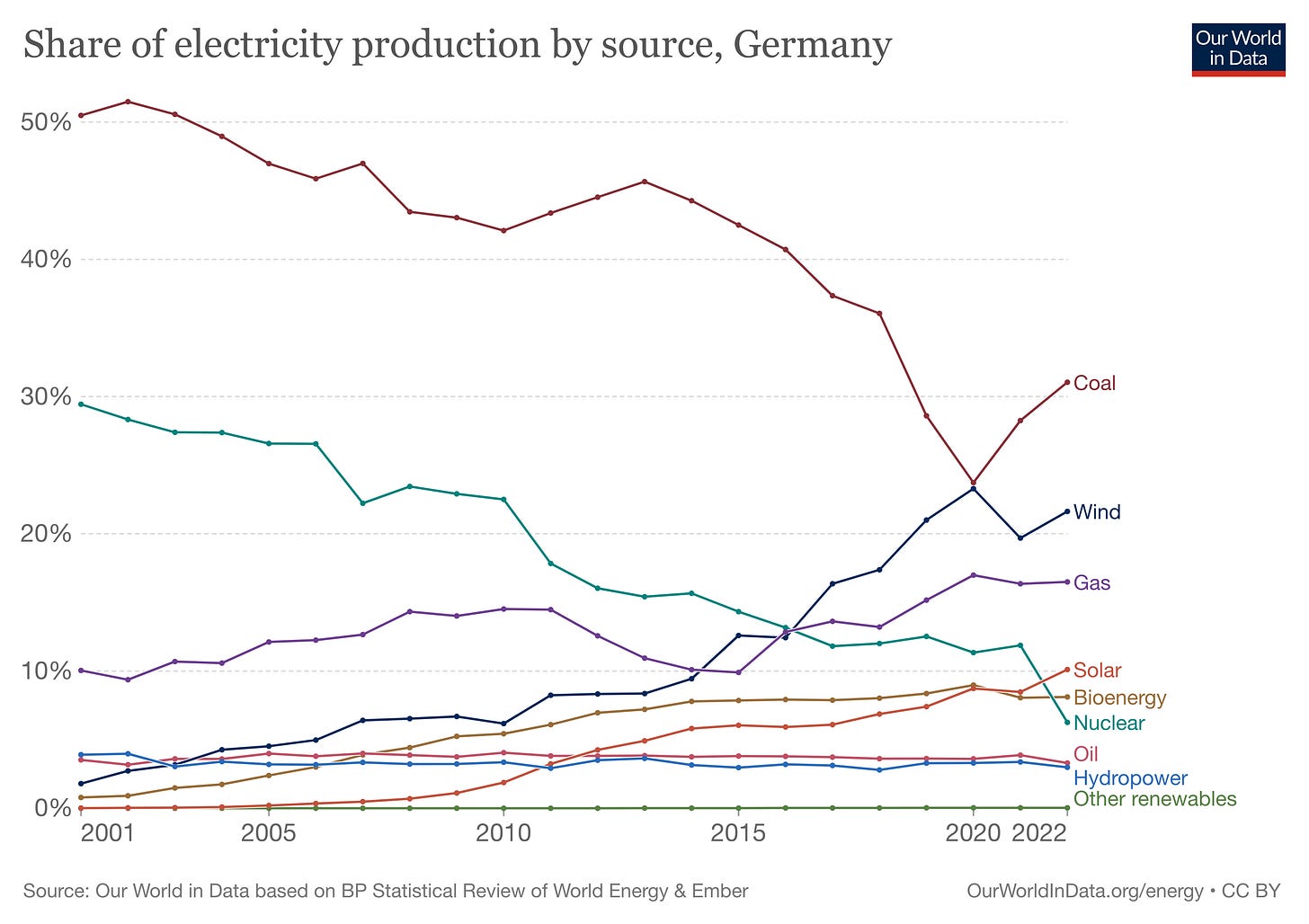

Let us not forget the impact that Fukushima had on Germany’s energy policy, Energiewende, with the ending of nuclear power becoming a central part of the country’s energy transition. From that we can think about Germany’s increasing reliance on Russia for its energy needs, which worked out really well… until it didn’t. And now Germany and Europe are being pulled back into the loving arms of the United States and its geopolitical games. It is worth keeping in mind the war in Ukraine is not just about the Ukraine… On this, Wolfgang Streeck suggests:

what we see coming as a result of the war, the Eurasian continent will be divided in an American and a Chinese section, with a heavily armed border confrontation at the eastern end of Eastern Europe and the western end of a Russia excluded from Europe.

The Fukushima nuclear accident happened during somewhat of a geopolitical lull: Obama was president and the war on terror was winding down, Hu Jintao was nearing the end of his rule and China’s rise was not yet a major source of concern, Putin was moving back from Prime Minister to President and had yet to adopt a more confrontational posture, and Europe was dealing with its ongoing economic crisis. The Arab Spring and the resultant conflicts in Syria and Libya were perhaps the most consequential events for international politics. And so, energy security was perhaps not accorded the importance it deserved. Yet, as the Doomberg substack rightly emphasises: ‘energy is life’. Indeed, it was precisely a recognition by the Japanese for the need for energy security that had motivated its adoption of nuclear, with the oil crises of the 1970s being an important driver in it expanding its fleet of reactors.

The development of Japan’s nuclear energy program was overseen by a succession of Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) governments, which has ruled Japan almost without interruption, except between 1993-94, and from 2009-12 when the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) ruled. And so, in a remarkable twist of fate, after having being almost exclusively responsible for the development and regulation of the nuclear industry, the LDP happened to be out of power when this structure failed spectacularly at Fukushima Dai-ichi. The DPJ was left holding the bag.

On the whole, Japan appears fortunate that Naoto Kan was Prime Minister when the nuclear accident occurred. I concur with Jeff Kingston’s judgement that Kan performed relatively well in difficult circumstances and was unfairly blamed. This conclusion is echoed by Kenji Kushida:

On balance, the DPJ and Kan were dealt a very difficult hand, and cannot be accused simply of crucially mismanaging the crisis…

Instead, the disaster revealed severe shortcomings in legal and bureaucratic organizational structures, contingency plans, information flows, and bureaucratic expertise. The political leadership did not unnecessarily intervene or hinder the rescue operations, and in fact played a critically beneficial role in coordinating various actors and facilitating information flows.

As Kingston explains, ‘personalizing the problem was an effort to downplay the fundamental institutional flaws that lay at the heart of the crisis.’

Kushida further observes:

Much of the blame-game after the crisis stabilized was an outgrowth of the LDP’s becoming a more effective opposition party, using the accident and broader Tohoku recovery issue as a means to successfully undermine the credibility of the DPJ.

And this brings us to one of the most under-appreciated consequences of the triple disasters. The LDP were able to successfully blame the DPJ for what happened. Kan was forced from power later in 2011, and in December 2012 the LDP returned to power in a landslide victory. And who became Prime Minister? The late Shinzo Abe, who would subsequently become Japan’s longest-serving prime minister. Along with Abe came Abenomics and Haruhiko Kuroda to the Governorship of the Bank of Japan, and all that has entailed.

The DPJ’s electoral victory in 2009 had offered the possibility of a genuinely competitive two-party system emerging in Japan. Following the DPJ’s electoral collapse in 2012, and subsequent disappearance in 2016, Japan has returned to a democracy dominated by one party, with other opposition parties proving to be remarkably ineffectual. And so, in 2023 the LDP is the only game in town, while the BOJ struggles with the policy legacies of Abe and Kuroda.

When the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear accident struck Japan on 11 March 2011, it was immediately clear that it would be profoundly consequential. What is remarkable is how deeply its legacies can be found in many of the key issues the world is grappling with in 2023.