Disposable world

Material, reality

I find myself in a disposable hotel, a place that could not have existed 10-15 years, and most likely will not exist again at some point in the near to medium term future when we are forced to consider more what we choose to build and consume. Almost every aspect of this hotel is a reflection of a globalised world in which energy has been historically cheap and abundant: from the fittings that were surely manufactured across Asia to the low cost airlines that fly in tourists to stay, arriving to give Japan’s economy that sugar high it so desperately craves.

This specific hotel was constructed in 2020, like many other such establishments that were built to capitalise on the Tokyo olympics and the boom in tourism the country was encouraging prior to the pandemic. Now the borders are open and tourism has bounced back, with around 2 million visitors coming in April. As in so many other areas, there is a rush to forget about the pandemic, including any potential useful lessons we could have learned, such as the downsides of over-tourism and the potential realisation that there are other ways of living and prioritising more sustainable arrangements. Never mind, lets get back to posting on socials.

The facade and roof of the hotel are made with steel. Given that Japan remains one of the world’s leading steel manufacturers, presumably this was made locally, but it would have had to import the raw materials necessary for producing the steel, most likely from my home country of Australia, based on this data:

Outside the hotel one also finds a share bike service, controlled by an app, allowing for the bikes to be used and returned to any of the parking areas across the city. Easy and convenient, no doubt. The bikes would have been made in East Asia, if not China, then Taiwan or Japan. Presumably the same with the electronics required for the app to access the bike. These products would have required source materials from across the world, and when finished, the finished products would have been put on a container and shipped to Japan.

Enter the hotel and one is greeted with the new scaled down version of omotenashi: the traditional Japanese conception of hospitality is now replaced with the not-so traditional tablet. The process of checking-in is outsourced, with the task split between the technology, the guest, and a person in a call centre somewhere in the digital void, whose disembodied voice speaks through the tablet to help me, because the check-in app does not work properly. Not only would this arrangement be cheaper than staffing the hotel, it is also a reflection of the labour shortages Japan presently has - and will increasingly suffer - in a range of service industries.

Once the check-in process is completed, I do not receive a key or a card, but a number on a screen, the pin code for my door. The digital nature of these interactions conceals the deep materiality on which it relies. This is explored by Guillaume Pitron in his new book, The Dark Cloud: How the Digital World is Costing the Earth, which details how digital technology ‘absorbs 10 per cent of the world’s electricity and represents nearly 4 per cent of the planet’s carbon dioxide emissions.’ The wireless experience I had with someone in a service centre is dependant on wires, data centres and energy.

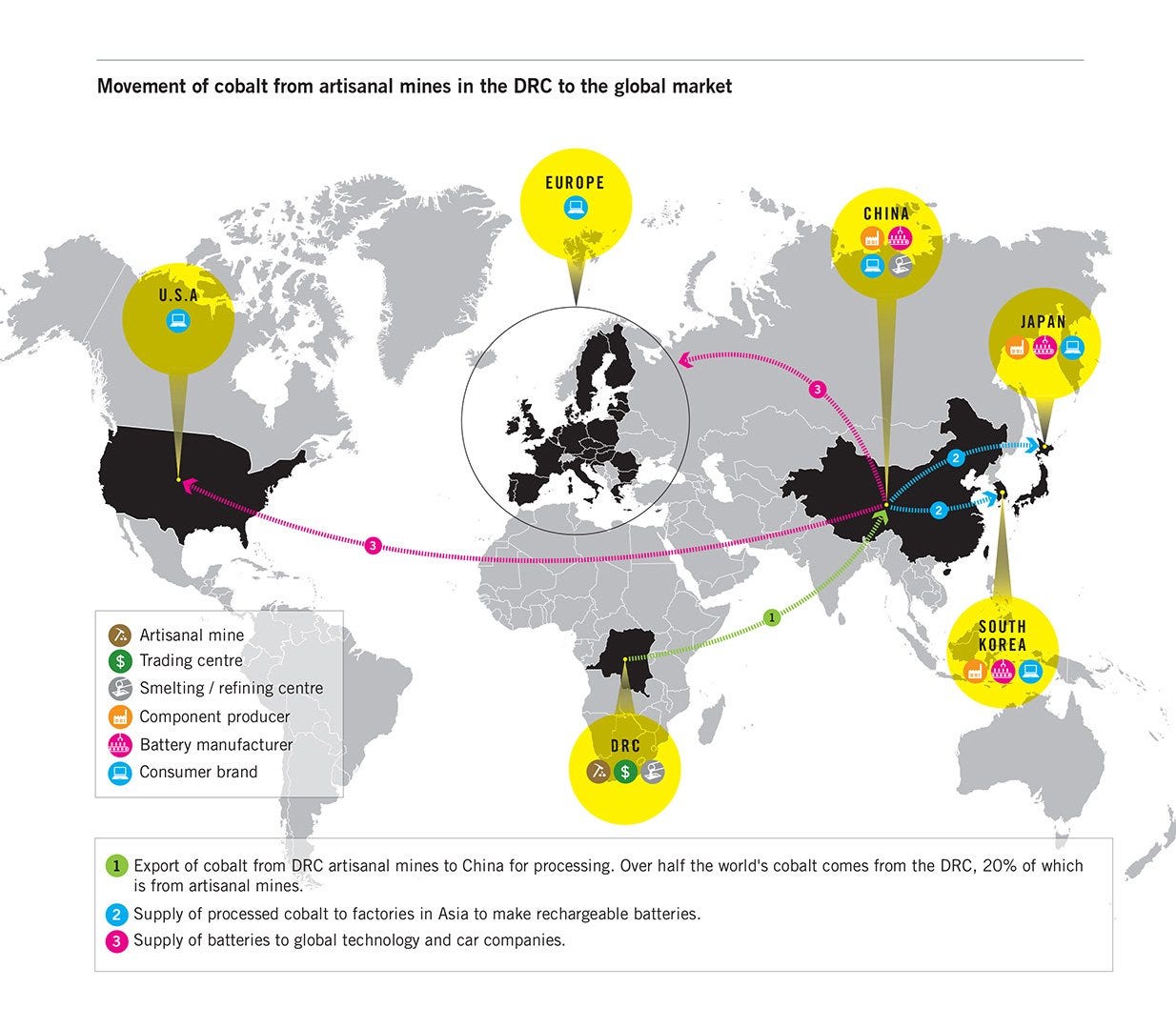

Returning to the tablet, it was presumably assembled in China or South East Asia, made up of semiconductors and other parts produced across the region, relying on minerals and resources sourced from the world. Most likely there must be some elements - perhaps in the tablet’s battery - that can be traced back to artisanal mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, dug out of the ground by one of the perhaps 100,000- 200,000 people working in terrible conditions. The below mapping of the supply chain from Amnesty International gives a sense of the connections likely present in the device.

On entering the room, I am greeted by various digital devices. Each would have reached here through some complex supply chain and production process, tightly linking together different countries and regions in ways it is difficult to comprehend. There is another tablet, a new tv, two mirrors with lights built-in, and the room has speakers ‘with natural sounds and music … taken from around Japan to create a unique experience.’ What is certain is that if we collectively continue to live in socio-economic systems that treat natural resources are infinitely exploitable, we will need these artificial reminders, because so much of our natural world will be lost and destroyed.

I could keep going, but the point is clear. This hotel only offers a particularly acute example of a fundamental feature of today’s world, namely, the extent to which so much of our economies and societies are structured around a complete disregard for material inputs. A digitised world of convenience is one that is constantly, voraciously consuming finite resources, and yet it is so difficult to see and recognise how profoundly unsustainable all of this is. Instead of looking around, we look down, back to the phone screen, click on another app and order another product, something that will have travelled in a shipping container to eventually reach a fulfilment centre where it waits for someone to click ‘buy’. And if it is not bought, it does not matter, but it is still matter, and it still matters. Regardless, it will just get dumped somewhere else. Moving from disposable hotels to fast fashion, one can find a particularly acute example of this dynamic. In both Ghana and Chile, there are enormous dumps of unwanted clothes, the one in the Atacama Desert being so big that it can be seen by satellite.

The challenge is keeping these material realities in mind when shopping and consuming, when enjoying the convenience that has come to condition our expectations. There is no easy solution to this disposable world of consumption and waste that we collectively live in and contribute to, but it seems a necessary step in moving towards something different must be better appreciating the material realities that give shape to our societies.

For those interested in thinking more about these issues, I would strongly recommend The Great Simplification with Nate Hagens, especially his conversations with Simon Michaux (part one, part two, part three).