To restate:

A world defined by acceleration, escalation, entropy, extraction and force. Behaviour shaped by anger, fear, greed, identity and ressentiment.

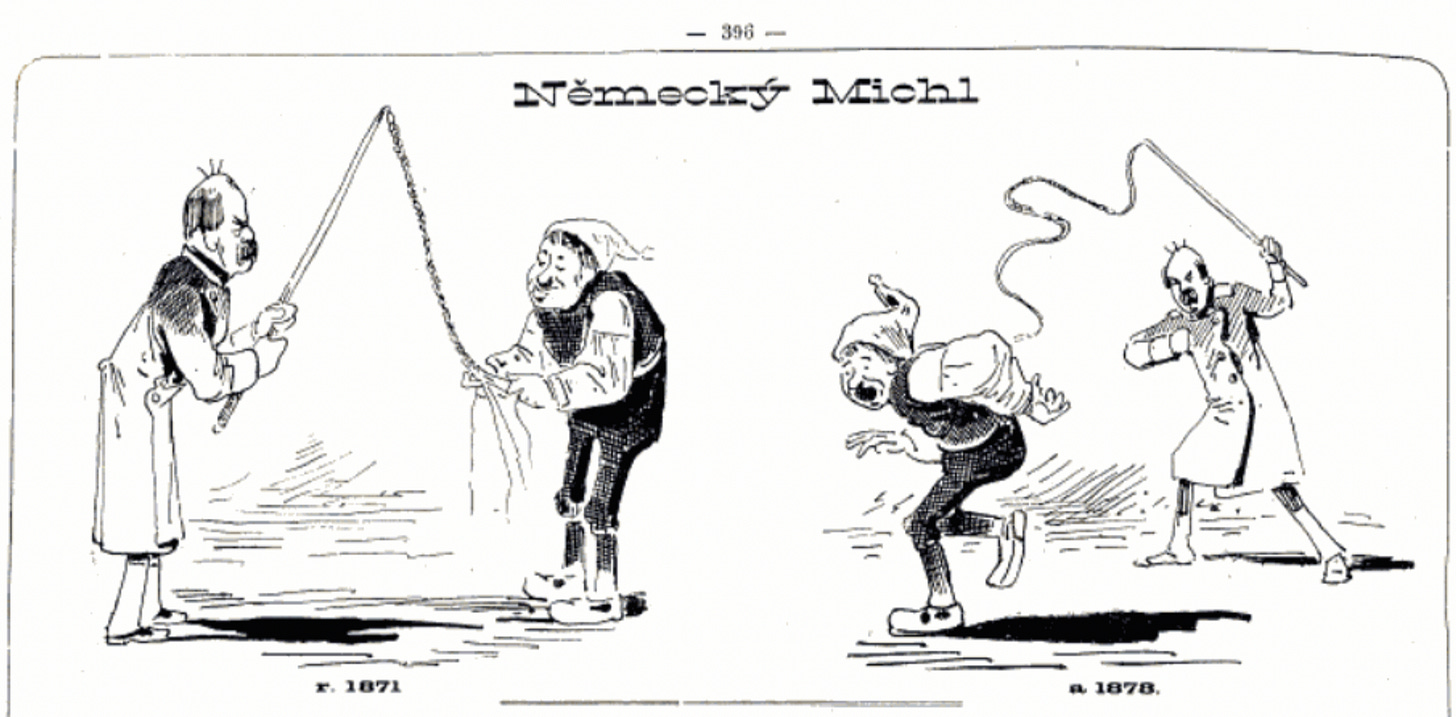

In Japanese, there is an expression ame to muchi ( 飴と鞭 ), which translates as ‘candy and whip’. Apparently this was taken from Otto von Bismarck’s expression of ‘zuckerbrot und peitsche’ (pastry / sugar bread and whip). These are generally equated with ‘carrot and stick’ in English, the basic idea of positive and negative incentives to shape behaviour. The difference, however, with the German and Japanese version is the sweetness of the reward (carrots might be tasty if you are a donkey, less so a human). And this leads to another interpretation I have come across: it is not a binary choice, but a pairing, ordered in a specific way.

After the whip, candy tastes so much better.

With that in mind, read Adam Tooze on: ‘“Oh ... it's only China”. Or how to make the sudden decoupling of the world’s two largest economies seem like a relief.’

Another Tooze note:

Something has happened to American political culture that divorces large parts of it from social reality. The result is that “cultural experiments” of the type that Trump and his gang are undertaking with the US economy are no longer shot down. The bubble is not burst. The madness is now everyone’s reality.

The analogue that is brought to mind is not so much the gerontocracy of the late Soviet Union as the delirium that followed in the post-Soviet 1990s.

the key point is that Trump’s tariff wars are not just unleashing economic experiments, but a fascinating cultural one, too: what is the American public’s attitude to pain? Will adversity be shared? And the longer that the US-China trade war grinds on, the more the stakes in these experiments will rise.

Daniel Ten Kate for Bloomberg:

Even after Trump announced a 90-day pause, it’s become clear that the US and China are reshaping the global economy to prepare for a war with each other that neither actually wants. Everyone else on the planet must deal with the fallout, while thinking long and hard about whether to trust either country — or to arm up themselves.

Xi Jinping and his comrades in the Communist Party share Trump’s goal of self-reliance. The Chinese leader has spent the better part of a decade trying to reduce his nation’s dependence on the US for strategic goods, just as successive US administrations have sought to prevent Beijing from obtaining high-end technology that could one day be used against American soldiers.

Yet the convergence between the two leaders appears to run deeper. In many ways, they both want what the other has: Trump desires China’s world-beating manufacturing prowess, and Xi is envious of the US’s control of advanced technology as well as the global financial system. And when it comes to style, both have shown a willingness to take drastic policy measures to achieve their goals, with little regard for markets.

To restate the key insight in that passage: ‘in many ways, they both want what the other has’. Meanwhile, the rest of the world gets squeezed. Well, if we are entering a world of lo-res game theory, at least we have lots of lo-res game theorists to go with it.

Eswar Prasad in the FT on deglobalisation:

Every country is fearful of becoming a dumping ground for each others’ exports…

If the US shuts its market and on the other side you have a huge economy [China] that is desperate to export because there is not enough domestic demand, that really creates a squeeze.

Given this note started with food, lets finish with the same theme. Consider that I might hope to bake an extremely delicious cake, or perhaps cook a satisfying meal. If I get the right ingredients, follow the recipe, have experience and so on, I might be able to achieve this. If, however, I randomly throw ingredients into a bowl, put it in an oven, pull it out, put it back in and so on, I probably will not achieve my aim.

And so, perhaps we really are left with the simple explanation, that this is policymaking in the mode of the Swedish Chef.