A bank run on meaning

AI and involution

One of the core aims of this project is to engage in the practice of open thinking. One of the constant challenges is doing so in conditions that actively impede thought and reflection. Swept up in reactivity and immediacy, weighed down by banality and stupidity.

Much of this note is based on some ideas about AI from about two years ago that I have yet to find the space to finish working through. I’m still not satisfied with how they are presented, nonetheless, it is time to share them.

Some more straightforward claims to begin:

LLMs and other present forms of AI might represent a new technological breakthrough, but certainly not without precedent. With Silicon Valley and the digital sector there is a very clear track record of performance, impact and consequence. When considering not only the economic, but also political, societal and cultural consequences, there is a history we can and should turn to. ‘Move fast and break things’ might work for software, it is a disaster for institutions and societies.

The most likely outcome is all this is more, Moore and MOAR: more energy use, more of Moore’s law, and more of MOAR consumption and extraction.

LLMs are an absolute disaster for education as presently institutionalised and practiced. It destroys the contract between teacher and student, poisons relations between students, and offers an easy out from something that is meant to involve difficulty and effort. I’m avoiding writing in detail about this, the only other thing I’ll add is the solution is pretty straightforward: some version of a small-scale teaching environment in which teachers can work closely with students, really get to know and guide them, and within that structured context AI tools may or may not be used. Such a response is, of course, completely incompatible with the educational institutions of scale we have, which are involuting at an accelerating rate.

There might be plenty of amazing advanced and developments that come with these technologies, but the likelihood that they will be used to advance humane and humanistic ends seems much less likely and more difficult to achieve.

Moving to more speculative claims:

Insofar as AI chatbots represent something like a calculator for words or thinking, this will greatly accelerate our transition to a post-literate world. One can assume we have passed peak literacy. Emojis and memes as post-modern hieroglyphs. I am fully in agreement with Erik Davis: things are only going to get much more weird (and cooked) from here.

AI will likely be highly deflationary in terms of producing content (words, images, music etc), but it might generate something like hyper-inflation for meaning. The process is roughly comparable: the destruction of value through over-supply.

Before developing these ideas further, first a crucial contextual point.

There is a tendency to separate out events across different sectors and regions, but when looking back on this decade, it will be important to recognise that the arrival of LLMs was coterminous with the COVID-19 pandemic. There was an overlap here we tend to forget about. Both experiences were - and remain - profoundly disorientating and disordering. In different ways, each has challenged and changed expectations about what is possible and what the future holds. These experiences and changes have left us feeling more insecure, more uncertain.

Arguing for the need to remember and reckon with the experience of COVID-19, David Wallace-Wells surmises: ‘the pandemic itself was real, and punishing. Above all, it revealed our vulnerability — biological, social and political.’ I have explored some similar themes in previous notes, ‘remembering to forget’. In a longer piece, Wallace-Wells points to the connection:

The emergency began at a time of geopolitical uncertainty, but it ended in an unmistakable polycrisis: beyond Covid, its supply shocks and inflation surge, there was a debt crisis and an ongoing climate emergency, wars in Europe and soon the Middle East and renewed great-power conflict with China.

At home the horizon flickered with the digital shimmer of an A.I. future, and accelerationists set about bringing it into being rather than succumb to pandemic privation or postpandemic stagnation.

In terms of AI, the pivotal moment was the release of ChatGPT 3.5 in November 2022, which also marked the anniversary of the emergence of the Omicron variant of COVID-19. This was a deeply disruptive period.

The Omicron wave followed by the GPT wave. Seeing these two developments as overlapping is especially relevant in the context of young adults and education. Students who already have had their learning disrupted and impacted by the pandemic also get to experience LLMs being let out into the wild, with basically zero regard for the consequences for schooling. Some kind of ideal-type AIs might be wonderful for learning and could possibly super-charge education. The real world AI that is out there right now - especially when paired with smartphones and social media - is a pedagogical disaster.

One of the observations I’ve been really struck by and struggling with is that as cultures, as societies, it appears we have lost our self-defence reflexes.

Now onto some other charts:

Considering the results of a recent OECD survey on adult skills, John Burn-Murdoch in the FT judges: ‘we appear to be looking less at the decline of reading per se, and more at a broader erosion in human capacity for mental focus and application.’ Indeed. It strikes me that research on the relationship between smartphones, social media and human development and social wellbeing is similar to when there was research emerging demonstrating a clear relationship between smoking and lung cancer, and later between fossil fuels and climate change. Findings that appear tentative or are contested will become widely accepted and acknowledged. Compared to these other examples, however, I’d suggest that when it comes to smartphones and social media, we do not need studies, we know it, we feel it, we see it. The impacts are really real.

To return again to this insight from Neil Postman:

Technological change is not additive; it is ecological… A new medium does not add something; it changes everything….

That is why we must be cautious about technological innovation. The consequences of technological change are always vast, often unpredictable and largely irreversible.

This brings me to a way of thinking about AI, an argument by analogy, thinking in reference to deflation, inflation, and hyperinflation.

…it is precisely because the events were so extreme that they are relevant.

Thomas J. Sargent, ‘The Ends of Four Big Inflations’ (1982)

AI is extremely deflationary in terms of drastically reducing the cost of producing text, images, video, sound and other symbols and representations. This is something we keenly understand: increasingly AI can produce content across all forms of media and culture. As the cost of producing content goes to near zero, it proliferates exponentially, perhaps leading to a ‘dead internet’, certainly already a ‘hostile internet’.

The corollary of this is something akin to the hyperinflation of meaning. The ‘value’ of symbols and signifiers collapse as they proliferate.

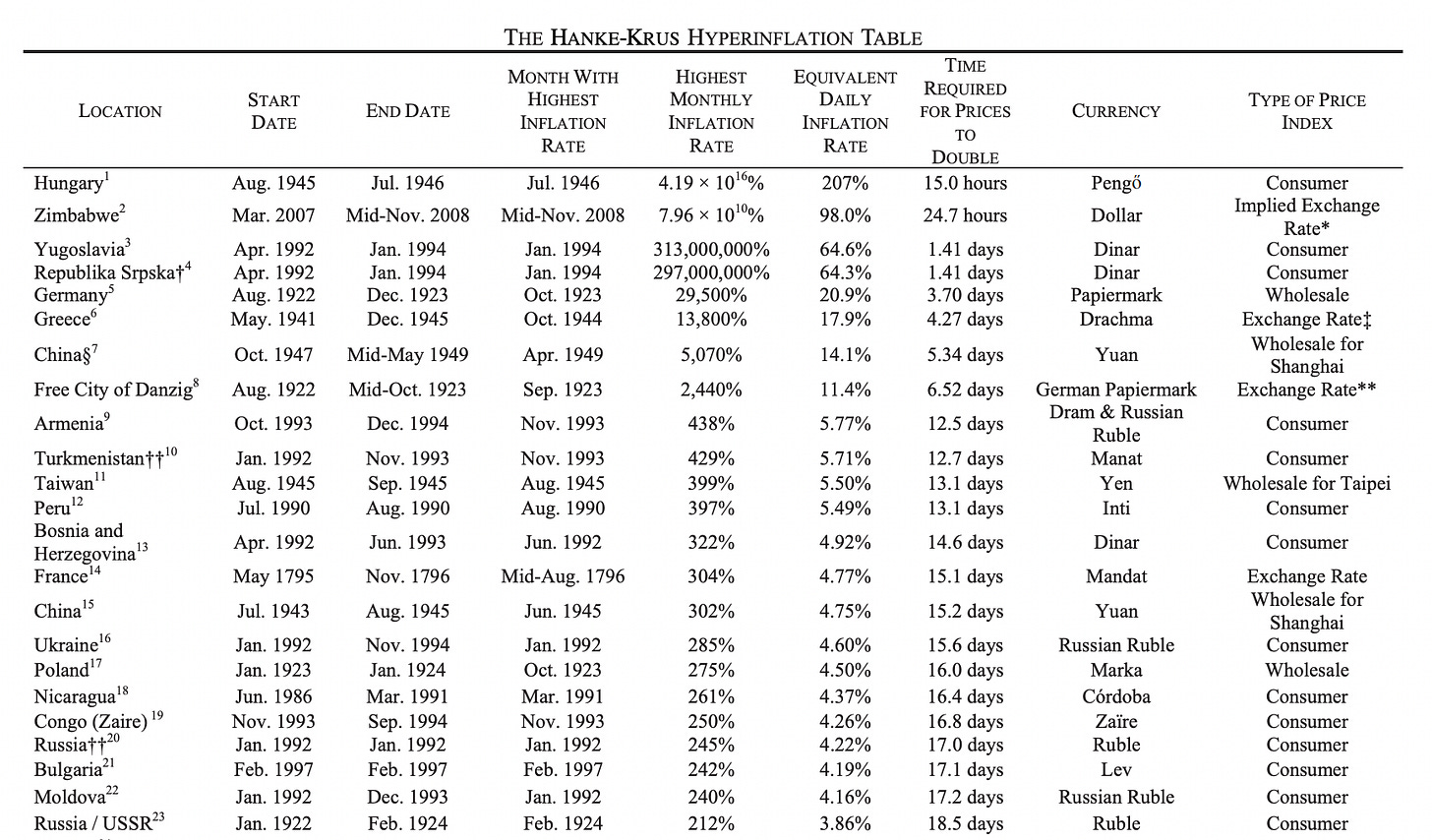

Thinking of AI, content and meaning, let us turn to the greatest instances of hyperinflation in the world. Steve H. Hanke and Nicholas Krus have compiled a list. The German post-WW1 experience is the most well known, but this is outstripped by the extreme extremes of Hungary, Zimbabwe and Yugoslavia. The full table is here, these are the top entries:

John Maynard Keynes wrote:

There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which no one in a million is able to diagnose.

And the best way to destroy culture is to debauch symbols and representations.

The master text for this is Jean Baudrillard, Simulations:

In this passage to a space whose curvature is no longer that of the real, nor of truth, the age of simulation thus begins with a liquidation of all referentials - worse: by their artificial resurrection in systems of signs, which are a more ductile material than meaning, in that they lend themselves to all systems of equivalence, all binary oppositions and all combinatory algebra.

It is no longer a question of imitation, nor of reduplication, nor even of parody. It is rather a question of substituting signs of the real for the real itself; that is, an operation to deter every real process by its operational double, a metastable, programmatic, perfect descriptive machine which provides all the signs of the real and short-circuits all its vicissitudes.

Never again will the real have to be produced: this is the vital function of the model in a system of death, or rather of anticipated resurrection which no longer leaves any chance even in the event of death. A hyperreal henceforth sheltered from the imaginary, and from any distinction between the real and the imaginary, leaving room only for the orbital recurrence of models and the simulated generation of difference.

In Hyperinflation: A World History, Liping He refers to an interview with Lenin published in The New York Times in 1919. The article has the subtitle: ‘Lenin is obsessed at present by a plan for the annihilation of the power of money in the world.’ This can be reworked, in the style of Baudrillard:

Silicon Valley is obsessed at present by a plan for the annihilation of the power of meaning in the world.

Care of Liping He, the mind-boggling case of hyperinflation in Hungary:

Keep this in mind when thinking of what AI-generated content is doing to the meaning and value of any text, image, sound or video online. Brave new world and all that.

Turning to Stefan Zweig’s description in The World of Yesterday of hyperinflation in Austria after WW1:

In consequence of this mad disorder the situation became more paradoxical and unmoral from week to week. A man who had been saving for forty years and who, furthermore, had patriotically invested his all in war bonds, became a beggar. A man who had debts became free of them. A man who respected the food rationing system starved; only one who disregarded it brazenly could eat his fill. A man schooled in bribery got ahead, if he speculated he profited. If a man sold at cost price, he was robbed, if he made careful calculation he yet cheated. Standards and values disappeared during this melting and evaporation of money; there was but one merit: to be clever, shrewd, unscrupulous, and to mount the racing horse instead of being trampled by it.

This can also be reworked:

Standards and values disappear during this melting and evaporation of meaning.

All of this is sketchy and speculative, but I fear not completely wrong, certainly not as wrong as it should be. To finish, the Soviet poet Osip Mandelstam:

The fact that the values of humanism have become rare now, as though removed from circulation and hidden, isn’t at all a bad sign. Humanistic values have merely gone underground and hoarded themselves away, like gold currency, but, like the gold supply, they secure the whole ideational commerce of contemporary Europe and from their underground administer it all the more authoritatively.